Bob Brown turned the key in the latch of his front door, gripped the lion’s-head knocker and pushed the door firmly to make sure it was locked. He felt a strong tickle in the top of his nose and reached into his overcoat pocket for his big Irish linen handkerchief. He sneezed into it violently. A few seconds later he blew into the hankie, wiped it back and forward under his nose, feeling wetness on his upper lip. He coughed into the hankie several times and looked into it to check for blood but there was none. He crumpled the cloth and stuffed it back into his pocket. Across the road, the herring-man clicked his tongue loudly to start his horse up the hill. He looked across at Bob but offered no greeting. Bob wasn’t too concerned about that. The man was one of the herring-chokers from Rosmoyle, and they were a queer lot. Most of them didn’t like Catholics but it didn’t stop them taking Catholic money. Bob was

Bob glanced up at the Union Jack fixed to his front wall between the two small windows of his front bedroom. The wire stringing the bunting across the street was anchored to one of the iron bolts supporting his spouting. The Orangemen as usual hadn’t asked for his permission but it wasn’t worth the bother to complain about it. It would all be taken down in about a month. Live and let live: it wasn’t costing him anything.

He passed the bar on the corner and walked across the road to go down

As he stepped through the ash, he met Joe McFee coming the other way. This man was the exception to Bob’s easygoing attitude to other people’s way of living. He was a drunken brute who beat his wife and children. Many’s a night Bob had been wakened by screams and the noise of doors being kicked from across the street. Unfortunately Bernadette McFee had no brothers who would have sorted this man out. Bob was astonished that all the other neighbours let it happen. He himself wasn’t fit enough to get involved.

‘Not bad. How’s yerself?’

‘Not so bad. Bob, ah’m a bit short at the minute. Ye cuddent see yer way te lendin us a coupla shilns till ah get ma dole nix Thursday, cuddya?’

Joe’s head jerked back suddenly. His eyes narrowed even further and the smile disappeared.

‘What goes onin ma house isnona yer f**kin concern. Keep yer f**kin money ye crabbit oul c**tye’.

He kicked at the ash around his right boot and a cloud of it splattered over Bob’s feet. He pushed his left shoulder against Bob’s and staggered past him onto the pavement at the bottom of

‘Sorry, got nothin on me’.

But at the same time he was glad he had at least said something unpleasant to the brute. He stopped, pulled his handkerchief from his pocket again and leaning over, flicked the ash as best he could from his shoes and the bottom of his trouser-legs. He replaced the hankie in his pocket and carried on down the hill. Five minutes later he was walking into

The shop was cooled by a large slowly-revolving fan in the centre of the high ceiling. A long oak counter ran the length of the wall on the left. Behind the counter, the shelves covered the wall right up to the ceiling. Each shelf was filled with a row of large glass or brown stone jars. Bob had always loved standing for a couple of minutes just looking along the shelves at the jars with their esoteric names lettered in gold leaf. Wonderful names. Centuries of chemistry, traditional and comfortably reassuring. Undoubtedly some of the preparations were no more effective than a lump of sugar, but the very strangeness of the names lent an authority to the contents, bringing the conviction that once the symptoms had been described to the pharmacist, his choice of jar would open the way to a certain cure.

Two people were waiting to be served, so Bob had time to run his eye along the shelves, to stare at the drawers at chest height with their brass handles and the equally impressive names printed in italic lettering on white card inside a brass rectangular frame.

‘Yes, Bob?’

It was Willie-John Ferguson himself, red-faced and jolly-looking.

‘Half-a-dozen Cullen’s powders. Ah’ve got a cold anna cough would rend rocks. Oh anna boxa Beecham’s Pills.’

There was now a woman standing behind Bob. He felt embarrassed.

‘No – they’re not for me.’

Minutes later, his purchases in a brown paper bag, Bob was walking along the street to the butcher’s. He bought a quarter-pound of stewing-steak and three pork sausages, all weighed on a set of gleaming white Avery scales. He handed over a ten-shilling note and received a fistful of change. As he left, he kicked each shoe in turn against the outside wall to dislodge the sawdust clinging to the soles. Blood had already started to seep through the paper around the steak, so he went back inside and got another sheet wrapped around it. He turned right out of the shop and walked the thirty yards to the door of Dunphy’s Bar.

The inside door was propped open by a big brass spittoon which had some cigarette butts floating in a liquid whose composition Bob chose not to think about. There was a heavy scattering of sawdust on the floor, with soggy wet patches in places. A heavy smoke haze filled in the single room. Bob walked straight to the bar. The barman was wiping spills off the counter with a grubby cloth. Bob waited until there was a dry patch and placed his parcel of meat on it. He leaned his walking stick against the bar with the bottom end dropped in behind the brass foot-rail. He took off his hat and put it on the seat of an empty high stool to his right.

‘What ye wantin?’

‘Bottla Guinness – Hughie Connor’s’.

The barman leaned back and lifted a bottle from a low shelf. Reaching up to the shelf above the counter, he took down a half-pint glass. He hooked the cap of the bottle into an opener under the counter and pushed the bottle down sharply. There was a hiss and then a light rattle as the cap fell into a metal bin on the floor. He held the glass almost horizontal in his left hand and slowly lifted the bottle, the neck just inside the edge of the glass. As the level of the Guinness gradually rose he raised the glass until it was finally upright. It was perfectly full with a two-inch head and he set it down carefully.

‘One an’ two’.

Bob took a small leather purse out of his trouser pocket. It had belonged to his wife Ethel. He pulled the stud that held it shut and the purse opened with a faint pop. He rummaged inside and took out two sixpences and two pennies which he dropped into the barman’s outstretched hand. He clicked the purse shut and shoved it back into his pocket and unbuttoned his overcoat, which he removed and draped over the back-rest of the stool. He picked up the glass of Guinness, raised it and took a drink which lowered the level by about a third. He put it back on the counter and turned to his left to look along the bar.

There was a whole clatter of customers in the room, standing or sitting at the bar. Others were ensconced at the long tables in front of the windows to either side of the entrance. Three men he didn’t know were playing darts in the corner where a door opened into the back area where the toilets were. The tables and the bar-top were dotted with well-filled ashtrays. A couple of brown sticky flypapers hung from the centre of the ceiling, each festooned with a substantial number of flies, some still twitching in doomed efforts to be free. Voices were loud and the exchanges were liberally peppered with swear-words. The room was hot and heavy with mixed smells of sweat, smoke and spilled beer. All of the customers were men and most of them were drinking stout. Occasionally a loud fart could be heard and no-one paid any heed.

One conversation caught his attention immediately. A thick-set man with a dark five-o’clock shadow was loudly denouncing the blowing-up the previous day of an electrical substation on the Newtownedward’s Road. Everybody knew it had been done by the IRA.

‘Anytime they arrest one of them bastards they should stringim up. Ye’d soon see then how brave these boyos are. They’d all be f**kin off outafit the same day.’

He paused to take a long swallow of stout. He wiped his moustache with the back of his left hand.

‘An there shudn be ennybody buyin Free State butter or shugger or nylons or anything else that they’re all peddlin across the border fer ivry Sunday. Hit them bastards in the South where they feel it the most – in their pockets.’

The man was called Johhny McIntosh and he’d been a B-Special. He was obviously drunk. Dunphy’s was Catholic-owned, but the Guinness was good and it was a mixed bar. People usually kept politics out of their conversations. You never knew just who might be taking exception to your views.

‘That’s anuffa the politics now’.

The barman slapped his hand on the counter.

‘It’s nothin te do with anybody here so stop bletherin and let people injoy their drinks! If you can’t conduct yerself, away home an spit in yer own ashes.’

One of the men sitting with McIntosh leaned over the table, and touched McIntosh’s elbow. He whispered something too low for anyone else to hear. McIntosh looked at him, took another swig of Guinness and sat back in his chair, staring sullenly at the barman. The momentary lull in conversation which had followed the barman’s shout ended and the buzz started up again.

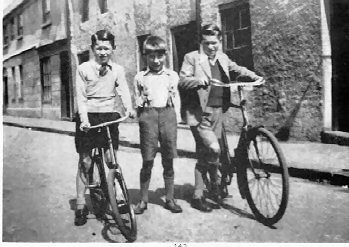

Bob had another drink of stout and thought about his planned cycle ride over the border tomorrow to do more or less what McIntosh had mentioned. He bought most of his butter and sugar and tea in the south in the little

‘Ah’ll have another bottle – by the neck’.

He poured the Guinness into the glass, waited for it to settle, and took a long drink. He belched as he put the glass down and automatically whispered ‘Pardon!’ Ethel had always shot him a dirty look when he rifted. She had never been in a pub in her life, had no idea how raucous and rude drinkers usually were. She used to say, ‘Ah hope ye don’t do that when yer out’. They had laid her down in the St Anne’s graveyard on a bitter December day. The minister had only spoken at the graveside for about three minutes, his white robe with the black streaks blowing wildly in the sleety wind. But when they tried to move the coffin, it was stuck fast to the ground, frozen solid to the yellow clay scattered around the open grave. It was almost as if she was unwilling to go. It took four of them to crack it free so they could lower her on the ropes. He took another drink. Life had changed after that. The house had gradually become a dump. When damp wallpaper began to peel down the walls he had fastened it back up with drawing-pins. He couldn’t be bothered buying paste and doing the job right. Some of the joists under the front-room floor had broken and the floor had sagged in the middle, what? – ten years ago? – and remained like that to this day. The heart had gone out of him. He finished the drink and ordered another.

He saw McIntosh get up from his chair and lumber through the door out to the toilets. A few seconds later, one of the dart-players followed him through the door. Bob stared idly at a noisy group of men playing poker for money at one of the window-tables under a notice on the wall which said, ‘No gambling permitted on these premises’. They were arguing loudly about something and everybody was examining their cards which were all fanned out face-upwards on the table. One of the players was stabbing a finger at one of the cards.

A couple of minutes later, the dart-player came back in. He said something to his mates and the three of them picked up their flat caps and shuffled out with a quick ‘Cheerio’ to the barman. Bob finished his drink in one go and decided it was time to leave. Just a quick piss before he went. McIntosh must have the skitters. The bogs would smell awful but Bob couldn’t hold out till he got home.

When he walked into the toilet, he stopped dead. McIntosh was sprawled in a sitting position with his back against the door-jamb of the WC. His head was slumped forward with his chin on his chest. His nose, mouth and chin were covered with what looked like strawberry jelly. The front of his shirt was wet with it too. The toilet door remained in the closed position because his right arm was raised against it and his hand was nailed to the door with a dart. The feathers were crushed and a trickle of blood was zig-zagging down his palm. He was groaning softly. His penis was sticking out of the front of his trousers. He was uncircumcised.

Bob backed out into the bar. He turned and leaned against the wall with the dart-board hanging on it. He felt sick.

‘Are ye all right?’

The barman was walking towards him. He lifted the counter-flap and stepped forward to touch Bob’s arm.

‘What?’

‘Are ye OK? Yer as white as a sheet’.

‘McIntosh’.

Bob jerked a thumb over his shoulder.

‘I’m away home, so among yez be it’.

He staggered past the barman. He picked up his parcels, hat and overcoat and stumbled out of the pub. He realised that he had left his stick behind. The sunlight hit his eyes and he closed them momentarily. He reeled a little as someone collided with him . He opened his eyes and recognised young Catherine Murphy from

‘Are ye all right, Mr Brown?’

‘What? Aye. Sorry, Catherine. Ah wasn’t lookin where ah was goin. Sorry’.

She smiled and walked on. He steadied himself. It was none of his business. McIntosh shoulda kept his big mouth shut. Bob could pick up his stick on Monday. They’d know it was his. He threw his coat over his shoulder and put on his hat. Without looking back, he turned the corner into

What a f**kin country.