Before Christmas I had cause, like many others to go up into the attic to retrieve the Christmas decorations. When I was up I decided to have a look at some of the old junk gathered there.

You know, all that old stuff that you can’t bring yourself to throw out, so, up into the attic it goes to spend the rest of its days gathering dust at the bottom of some cardboard box.

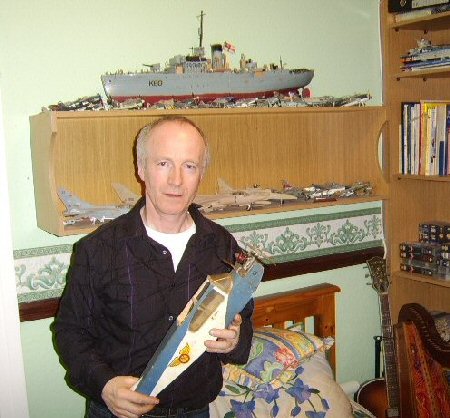

During the course of my rummaging around I happened to come across one of my old model aircraft. It was a balsa wood free flight model that was assembled from a Keil Kraft kit. The sight of that old model aeroplane transported me back to my childhood days. Way back then I had a passion for building models: ships, aircraft, tanks and all sorts of military vehicles.

Like the ubiquitous Dandy and Beano comics of those days, there were some other toy product names that could cause any post-war child to drool with excitement and anticipation: names like Hornby, Meccano, Airfix, and Raleigh to name but three. But to the discerning builder of rubber-powered flying model aircraft, we also had model kit manufacturers such as Keil Kraft and Frogg.

That old broken balsa wood model that I resurrected from the dark depths of our attic was a Keil Kraft high-winged monoplane Piper Cub. It was the last balsa wood flying model that I ever made. Also it was the only model that I ever constructed that was powered by a two-stroke internal combustion engine! All the rest were either gliders or more usually, rubber-band powered.

A rubber band power source was all that most children in our locality could afford at that time. But this particular model plane was built when I was a more affluent working teenager, so it was endowed with a real power plant, i.e. a proper miniature two-stroke engine. The engine of my model aircraft was fuelled by a two-stroke mixture of methanol and castor oil. This mixture went by the name of glow-fuel. You can also get diesel and petrol two-stroke engines for model aircraft, but they are generally used for control-line and radio-controlled models. The reason for this is that the diesel and petrol varieties are more controllable in that the engine can be advanced or retarded for speed control, but the glow-fuelled two-stroke motor can not be retarded. This means it has an engine that can virtually only be run flat-out.

A lot of fifties and sixties children played with balsawood gliders and rubber-powered planes at some time in their youth, just as I did. Whether it was a toy that your mum or dad bought you for ‘being good’ … a birthday present … or something you spent your pocket money on in order to have some fun with friends on a sunny, summer’s day. Balsa airplanes have been around for many years and are one of the time-tested toys that all children remember with affection. The joy of flying these model airplanes and watching as they swoop and glide through the air made them some of the most exciting toys we had. Simple, inexpensive and fun, these planes could help pass an entire summer afternoon.

The construction of flying models is very different from most static models. Flying models borrow construction techniques from real full-sized aircraft (although models rarely use metal structures.) These might consist of forming the frame of the model using thin strips of light wood such as balsa then covering it with tissue paper and subsequently doping the tissue to form a light and sturdy frame which is also airtight.

Flying models are usually what is meant by the term aeromodelling. Most flying model aircraft can be placed in one of three groups:

Free flight (F/F) model aircraft fly without any attachment to the ground.

This type of model pre-dates the efforts of the Wright Brothers and other pioneers.

Control line (C/L) model aircraft use cables (usually two) leading from the wing to the pilot. A variation of this system is the Round-the-pole flying (RTP) model.

Radio-controlled aircraft have a transmitter operated by the pilot on the ground, sending signals to a receiver in the craft.

As a young lad all those years ago it was the free flight model out of the three types described above that really caught my imagination. Control line and radio-controlled aircraft were not powered by a rubber band they required a real working motor which was much too expensive for me at that age, and as for radio-controlled, I could forget that completely.

I remember whenever I saved up a few shillings pocket money, off I went hurrying down to that wonderful Aladdin’s cave, the venerable Lockhart’s toyshop on

After making my purchase I would hurry home, as I was always dreadfully keen to start building my new model aeroplane. Building those balsa wood kit models was every bit as enjoyable as flying them.

Inside the box that the model came in you would find: a set of assembly drawings (plans), a roll of tissue paper, plus all the lengths of balsa wood required.

First I had to commandeer the kitchen table and then set out the assembly plans. I would pine the plans down on to a large wooden board that I kept especially for that purpose. Then I would carefully cut all the little pieces of balsa as they were needed, lay them down on top of the drawing and carefully glue them in place.

The whole building operation could be a long process taking perhaps a few days so I had to be prepared to vacate the kitchen table when my Mum needed the use of it. That was the idea of doing the construction and using a large wooden board to work on. When I had to stop working on my model for any length of time then all I had to do was scoop up the loose pieces of balsa so that they could be returned to their box. As for the board with the plans pinned to it, plus the part-finished aeroplane, well, it could quite easily be slid under my bed. That way everything was tidily tucked away until I was able to resume work again.

When you finally have the fuselage, wings and tail plane of the model completed it is now time to cover the structure. For this you use the tissue paper supplied with the kit. With this tissue paper you cover the entire aircraft including wings and tail. The tissue paper was stuck to the balsa wood using white or clear glue. Then comes the tricky part! All of the tissue has to be covered lightly with a clear dope. The dope when it dries out has the effect of stretching the tissue paper tight over the wooden structure: so tight in fact is the doped tissue paper that it resembles the skin of a drum.

You had to be very careful when doping the model because if you applied too much dope you were in great danger of warping the structure. The wings especially needed careful attention. It was always better to keep the wings pinned flat down to the wooden board during doping and leave them pinned down until after the dope had well and truly dried out.

At last comes the big day when your model aircraft is ready for its maiden flight! Finally you will see your little plane take to the sky, you will watch as it soars on high, riding the thermals, defying gravity for that short space of time and then gliding gracefully back once more to earth.

The construction of flying model aircraft is not all that dissimilar to the building of the real full size airplane. In the 1965 film The Flight of the

Real craft skills, those that are not casually or easily learned, can provide a child with hours of fun, and offer one thing more: pride in a true accomplishment. A child who has built a real stick-and-tissue model airplane, one that really flies and flies well, will feel pride not only in ownership and use of the new toy, but also pride in the ownership of a new, larger self.

These are lasting experiences,

the basis of genuine self-esteem.