Awareness that a whole social and sporting culture existed of which I was not – and apparently could not – be a part, soon followed.

Gaelic football, hurling and camogie began to be mentioned in conversations in

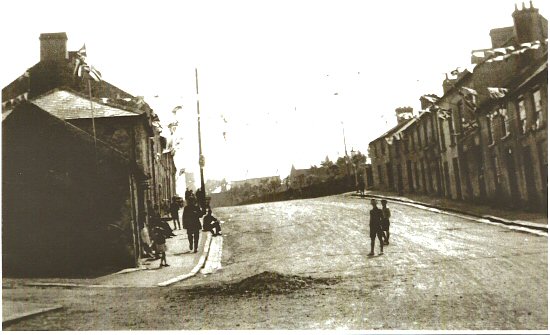

Cowan Street was a mixed working-class community in Newry’s North Ward. On top of the hill, St Patrick’s looked down on most of the town. Jonathan Swift’s epithet, ‘high church, low steeple’ was a constant reminder that church was a dominant feature in people’s lives.

In the 1950’s the ringing of St Patrick’s bell on Sunday mornings brought worshippers from all over Newry. I knew however, that if I could stay in bed until the ringing began, then I could avoid having to go to St Mary’s down by the market, because I wouldn’t get there before the service started.

Protestant my family might have been, but church attendance was at best sporadic.

Anyway, friends who went to the Presbyterian churches in town assured me on a regular basis that I wasn’t a real Protestant, since there was ‘only a paper wall’ between the

In a subtle way also, I think, this reinforced the reality that I had much more in common with Catholic friends in my immediate area than with Protestants in the wider community. Lavatories in the back yard and a cold water tap outside the back door and visits to the pawn shop, tend to be shared realities which make the posturing of politicians and the leaders of organisations rather irrelevant to the processes of daily life.

Daily doses of Radio Eireann before school added to this, and ‘The Walton Programme’ with ‘The Songs our Fathers Loved’ together with the somewhat arcane agricultural advertisements of ‘Whelahans of Finglass’ ensured that my life-view was not narrow and Northern-orientated.

Without my knowing it, my sense of Irishness was developing.

Not being ‘