As in most callings there were two or three classes of pedlars. The King of Pedlars was the man who, with a tidy balance at the bank, and an account with some great wholesale drapery house, usually drove a van with a horse along the principal roads of the country and disdained to call on any person lower than the rank of strong farmer. As a rule he was loud, pushing and loquacious, a good salesman and a decent fellow all round.

Then came the pedlar who drove a mule or donkey-cart and who also frequented fairs where his gaudily-decked booth containing coloured, cotton handkerchiefs, cheap muslin and articles of small ware, was a prominent feature. He was more or less looked down on by the big man who drove his horse; but the man with the mule had in turn a corresponding contempt for the poorer brother who, with his pack strapped over his shoulders, sought the favour of his customers on foot. But the latter wayfarer had one advantage over his bigger brethren. He could, and did penetrate further into isolated districts and so reap many small orders from clients who were not so much in touch with highways.

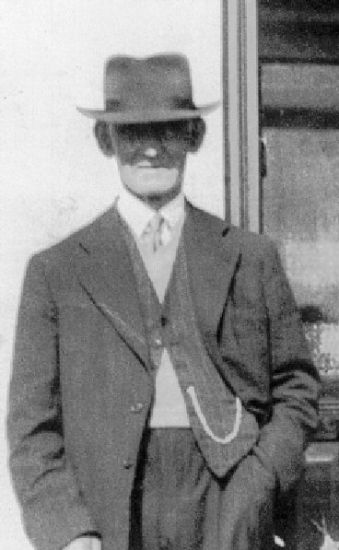

And in truth this latter specimen of the tribe was the most interesting of the lot. He was generally past middle-life with the healthy, hardy glow in his countenance that much living in the open air usually gives. His face seemed so open and truthful that it was difficult to believe he could over-praise his goods or over-reach one in a bargain.

But with all that our pedlar was a man with the shrewd eye to the main chance. It was pleasant to see him approach the open door of the farm-house, and if the time was evening and he contemplated resting for the night, his greeting was doubly voluble and gushing: