There has always been a unique relationship between Ireland and France. For centuries Irishmen served the Fleur-de-Lys by the sword and in so doing sought to serve the shamrock. Irishman Brendan Cassidy served France …

… by fostering a love of her language and culture, her customs and her people in generations of Irish schoolchildren and later in children attending the European School in Brussels.

Brendan was born on the Limestone Road in north Belfast in 1933. He was a promising pupil in primary school and won a scholarship to St. Malachy’s College, Belfast’s prestigious Christian Brothers Grammar School. In addition to being academically bright he was an outstanding athlete and played on the school Gaelic football McCrory Cup team although all-Ireland success was to elude him.

In later years he was to play soccer professionally for Newry Town FC. Brendan won a scholarship to Queens University in 1951. After his graduation with a BA in modern languages he taught English for a year in Belfort (Alsace-Lorraine); he was later to return to France with his young family to L’Orient, Britanny. He made and retained many French and Breton friends. Through these experiences he achieved native fluency in the French language that was to become the passion of his life. Brendan had met Molly at a ceili in St. Joseph’s Youth Club on the Antrim Road in 1952. They were married in 1957 and were blessed with four children, Anne-Marie, Terry, Jacqueline and Philip.

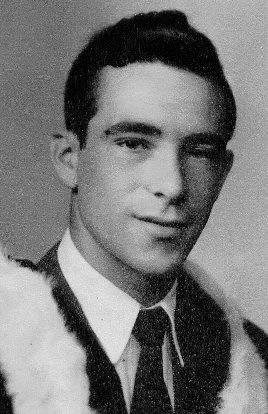

In 1957 Brendan took up a post in the Abbey CBS where the gentle Brother Mullins was principal. I started my secondary education in the Abbey in September 1958; Brendan was my French teacher and was to be so until I left in 1965. From the outset we first-year pupils were fascinated by him; his softly modulated north Belfast accent was scarcely less exotic to us than would have been that of a real French national. That combined with his dark good looks and stylish if slightly bohemian dress sense gave rise to rumours among us that he was indeed “un vrai francais”.

Whatever the nationality it was clear to us that Brendan was a superb teacher. If there was one adjective I could apply to his teaching it was meticulous. His preparation was meticulous, as was his attendance. His presentation and explanation of grammar were meticulous, his corrections were meticulous and above all he was meticulously fair. In an age when corporal punishment was the order of the day Brendan used the strap only sparingly and with minimal force. Such was the respect in which he was held that pupils seldom misbehaved in his class.

Moreover it was pointless to miss homework, as he relentlessly recorded omissions and followed them up until they were completed. If this makes him sound somewhat robotic then such was certainly not the case. Brendan was in every sense a complete and warm human being. Reserved to the point of shyness he gradually warmed to our class and us to him; he heaped praise on us and compared us favourably to other classes. On the rare occasions when someone did overstep the mark he would flush deeply and pause before administering a sharp oral rebuke which invariably produced the desired effect.

I have already referred to Brendan Cassidy’s sporting prowess. I truly believe had he not become a teacher (or professional footballer) he could easily have been an actor or even a dancer. His lucid explanations of obtuse grammatical subtleties, his readings of Ronsard, Hugo or Lamartine were delivered with voice and facial expression synchronised, to convey as appropriate, subtlety, intensity, persuasiveness, passion or precision, further emphasised by graceful and intricate hand and arm gestures and even appropriate posture. Writing at the board he would often stand sideways usually with one hand in his pocket, knees slightly bent, not unlike a profiled relief of the “Depart Des Volontaires” on the Arc de Triomphe. In that somewhat tortuous stance he could keep one eye on the board, the other on his restless flock. Thus it was that every lesson seemed to us a performance delivered with grace but without gimmickry.

Brendan was an early exponent of modern methods though overall his approach owed more to Chomsky than Skinner. He played us recordings of native French speakers, taught us songs and rhymes, ordered French magazines, puzzles, crosswords and comic strips. Class readers supplemented the competent but somewhat turgid Whitmarsh coursebook. His knowledge of French geography, literature, history and culture was encyclopaedic and passionate; he shared it with us unstintingly, along with his own photos, slides shows, cine film and above all personal anecdotes. He organised trips to France; those of us unable to afford them nevertheless shared the experience when subsequently he would present a cine show on the group’s return. Through his efforts and those of other gifted linguists (unfortunately too numerous to mention) on its teaching staff, the Abbey Grammar School became a veritable centre of linguistic excellence offering French, Gaeilge, German, Latin, and Spanish at A-level. When I went to Queens in 1965 I remember our French lecturer expressing surprise at the size of the Newry contingent that had opted for French.

Brendan left the Abbey in the early 70’s to teach in St. Mary’s CBS Belfast in difficult and dangerous times; after three years he emigrated to take up a teaching post in the European School in Brussels where he soon acquired a reputation for outstanding teaching, professional integrity, independence of mind and scrupulous fairness. In 1990 he returned to Ireland having been appointed language adviser with the Western Education and Library Board based in Omagh, a post which he held until his retirement in the mid 1990s.

It was in his language advisory capacity that I last met Brendan some 15 years ago at a training course. We had both of course aged considerably but recognised each other right away to our mutual delight. I told him publicly and in no uncertain terms that he was undoubtedly the best teacher I could have hoped for and how much I appreciated all that he had done for me. He coloured up with a mixture of embarrassment and delight and responded with that ear-to-ear schoolboyish grin for which I shall always remember him.

In 1998 came the Omagh bombing. Brendan offered his services as interpreter to the Spanish families caught up in the horror. For several hectic days he used his own car to commute frantically between Omagh, Belfast Airport and Buncrana, refusing all payment even petrol expenses. Whether the trauma of those dreadful days contributed to his final long illness we shall never know.

Brendan died peacefully on the 23rd September 2010 surrounded by his devoted family. He is survived by his wife Molly, children Anne-Marie, Jacqueline, Terry and Philip, and by five beautiful grandchildren Jessica, Emma, Lorcan, Aoife and Michael; he is also deeply mourned by his sister Lola and brothers Pat, Michael and Terry.

Solas De ar a anam uasal, ni fheicfear a leitheid aris *

(*God rest his soul, his equal shall never be seen again)