Bojo Rides Again!

In Camberwell, East, where the money tree grows Bozo was snorting coke straight…

Act of God

I hesitated to ascribe the previous story to an ‘act of God’. Not so this one.

‘The hillside was a well-known area for young lovers,’ explained the police chief. ‘Unfortunately it also attracts voyeurs spying on their antics.

These three men were peeping toms who liked to hide in an old broken-down hut, in which they had installed a high-powered telescope. Yesterday afternoon all three were watching a young couple having sex in their car. They were so engrossed that they failed to notice an electrical storm had begun.

A bolt of lightning struck the telescope’s metal casing. All three were hit at the same time and only survived because they shared the impact of the super-high voltage. All three suffered serious burns to their hands and legs and could not talk for hours from shock.

We let them off with a caution. They had been punished enough.

I don’t know about the young couple, but I believe the earth moved for these three’, he added, rather unsympathetically.

Gerry Monaghan’s memories:10

Gerry Monaghan’s Memories 10

Mindful of its gloomy history, I have always regarded the quarry with thoughtful apprehension. Despite this, as an older boy I would go fishing for spricks (sticklebacks) in its clouded, enigmatic waters. The spricks were much bigger here and so more desirable. Later as teenagers, filled with the wild daring of that capricious age, we actually swam there. We would climb down the rocks to a ledge just above water level. The ledge afforded space for our clothes and allowed us to bask when the sun shone. Sheltered as it was by the high surrounding rocks, it then became a sun trap. From this ledge we would manfully plunge into the water, mindless of its awesome depth. We would then splash about with the clamorous exuberance of youth, shouting lustily, amused by the repeating echoes from the rocks around. Yet despite our apparent dare-devil abandonment, the water’s deep menace lurked in our minds like a prowling shark. When a swimmer occasionally felt some unthinkable, aquatic abomination touch his foot, all dare-devil pretence vanished in a frenzied flurry of white water as the would-be Tarzan swam frantically, flailing the water, seeking the safety of the ledge.

There were a half dozen disused granite quarries in this area and we had swum in several. Most, at some time or another had claimed the lives of boys. But my narrative has jumped ahead of its time. In the interests of clarity I will return to the year the war began.

First a word about my brothers and how we related to one another. Edmund was the eldest. He was then about ten years old. He and I had always been coupled, our names linked. Edmund had always had a special relationship with mother, perhaps because he was her first. She spent more time in conversation with him than with any one else. She also demanded more of him, expecting him to shoulder more responsibility. She was always quicker to blame him if anything went wrong with the boys outside. He was responsible, and generous with the rest of us, but could be forceful – not so much with me as with our other brothers.

Donal, two years younger than me, soon outgrew me. He was ebullient and big for his age, but soft. My aunt Alice used to say, ‘He’ll be a big policeman when he grows up.’ Curiously Donal had never become linked with another brother, as Edmund and I, or Gerry, or Brian and Dermot. I guess this was because Brian, his immediate subordinate (age-wise) and natural link was, like Donal himself, extremely independent and single-minded. Therefore the two could never mesh.

Edmund and I used to annoy Donal, who was tall for his age and very thin, as we undressed for bed. Using our fingers and making the appropriate sounds we would pretend to strum his ribs, harp-like. Of course he resented this and would pull away complaining to our mother. She would not allow sibling mockery but would often be too busy to prevent it entirely. Despite – or perhaps because of – the leg-pulling he sometimes suffered, Donal became very resourceful and ambitious and unlike the rest of us, very astute in the commercial sense.

We were all usually put to bed at nine. The younger boys occupied the double bed in the large back room while Edmund and I slept in the small back room. Sometimes just for mischief after we retired, we would decide to frighten the younger lads. One – usually Edmund- would sneak into our parents’ bedroom before they retired. In the wardrobe my mother had an old fur coat which suited our purposes admirably. Shrouded in this frightening bear-like disguise Edmund would creep towards the bedroom door of our innocent, unsuspecting younger brothers. The door would creak as he slowly pushed it open. Then moaning barely audibly he would slowly slither towards the bed. Of course they suspected it was us but boyish imagination often overcomes mere logic and they were also inhibited by the puerile pride that boys have in never showing fear. Imagination aided by the shades of night is fertile ground for fear. Their nerves would finally break, pride would be ripped away by the dark claws of terror, the gloom would be rent with their unnerved, quavering voices crying, ‘Mammy, these fellas are scaring us.’ This would be hilarious to Edmund and me. We could hardly contain our stifled mirth. Hearing the commotion, mother would come to the bottom of the stairs.

Speaking slowly and quietly in a firm voice loaded with threat, she would say, ‘If I have to come up these stairs you will both be sorry. Don’t let me hear another sound.’ At this she would return to the living-room closing the door quietly behind her. We knew that she knew who was at fault and that was enough. We knew she meant every word and we stopped our fooling at once. Lions and tigers are undoubtedly frightening beasts but they are far away. Mother was close and when aroused, every bit as fearsome.

With four energetic and often fractious boys and a young child, mother had her hands full. While father was at work she was busy with the cooking, cleaning and running the home. During the normal day we would all be at home only at meal times. The worst time for mother, her patience would be sorely tested. Sitting around the table waiting, with noisy banter, we wanted to eat to get out again quickly, oblivious of her labours. The older boys were always teasing the younger ones who would complain loudly. That would do it and mother’s reaction was fierce. With one hand on the loaf she would turn, her face like thunder, the bread knife poised in her other hand, and say, ‘If you do not behave yourself, I’ll give you a nick of this knife!’ This had an immediate sobering effect on the miscreant being addressed, and to us all. This small, volatile woman was not to be toyed with. We all knew that she was capable of anything. She might throw the knife, or a spoon, or anything that came to hand. She had done it before. Fortunately like most women she was no good at throwing things, not very accurate, so no one ever got a knife in the chest of in the back as he dived for the door. However it was a realistic hazard, and it concentrated our minds, causing us to moderate our thoughtless behaviour.

Father was usually absent at work, but even when he was there, it was mother who was the disciplinarian. As an indulged only son, father’s own relaxed upbringing ill-prepared him for his role as the head of a large family. He did not understand sibling rivalry or the devious machinations of juvenile politics. He seemed unaware of the acute perceptions of kids in spotting parental weakness and their unflagging persistence. Fuss and clamour overburdened his unworldly mind so that he would part with anything in the interests of peace.

Even as a toddler Edmund perceived dad’s weakness. On one occasion when mother had gone out to the shop and left father in charge, Edmund took advantage of mother’s absence by demanding of father, ‘Daddy, I want that clock!’ as he pointed, to dad’s dismay, to the clock on the mantelpiece.

In the year that the war began Donal was old enough to attend the convent school. As I was still at the same school I offered to take him. As the school was on the same street mother allowed this. Off we went hand in hand. When we reached the school a few minutes later I brought him directly to the babies’ class. It was on the ground floor, in the small enclosed yard beside the fire escape. Opening the classroom door, I pushed him firmly inside and, without a word, closed the door. I then went to my own class. So you see, Donal had been injected into the school rather than introduced. A few days later in the middle of the morning as mother went about her chores, to her surprise Donal came bouncing in unexpectedly from school. His brown eyes were dancing in his head as he exclaimed, ‘Mammy, I’ve bracted out! I’ve bracted out!’

Two years younger than Donal, Brian was then about three years old. Even at this young age his character and temperament could clearly be discerned. He was single-minded and stubborn, but quiet if left alone. If his animosity was aroused he could be quite intractable. Brian did not like fuss of any kind, especially if it was directed at him. If there was a family gathering or party that perhaps entailed taking photographs, Brian could become truculent , especially if he was put under pressure to submit or conform. He would howl belligerently and would not submit. Aunt Theresa often referred to him as the ‘Young Turk’. As a result, in family photos of this era, Brian is often depicted with his knuckles in his eyes, crying.

Because of these traits he was often left to his own devices, which pleased him. Always short on words, he was however very dependable.

Dermot was just a baby at this time. He is the only one whose birth I remember. All the others seemed to have always been there. I remember mother being confined in the house. There was lots of quiet, urgent babble. Then I remember going upstairs to the front room to see the new baby that my mother had received, I believed, from the doctor. She looked tired and wan, but she was there smiling with the baby at her side. Although I understood the baby to be new, it looked old and worn. Apart from curiosity, I cannot remember feeling any great tides of emotion at the time.

At The Seaside: Gerry Monaghan

6. Fun of the Fair

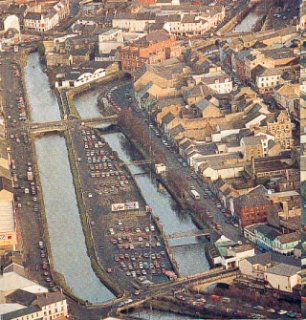

How bright the light is near the sea! We look down upon the fishing boats lying askew on the shining mud. Above these, the drunken tangle of wayward masts, around which graceful gulls glide, tirelessly wheeling, their hungry eyes questing, forever complaining as if they felt perpetually victimized.

A cargo boat sits on the wet sand, leaning slightly against the dockside, its rusty hull exposed to the ministrations of two crewmen with long brushes, in a never-ending struggle against the sea’s perpetual corrosion. But above all it is the strong, salty tang of decaying seaweed in the bracing air that proclaims the sea and its wide, bright, alien fascination.

Last Bessbrook Tram

Last Run on Bessbrook and Newry Tramway

One local reporter shared the last tram run to Bessbrook, as it set out from the Edward Street terminus in January 1948, with a young boy, and one man and one woman. This is his story.

In answer to his query, Mrs Hannah J Copeland replied that departure time was five thirty.

‘You mustn’t be on the tram often or you’d know the time she goes?’

‘No. I’ve never been on it before and I’m all my life in Newry’, I answered.

‘Well, you’ll never be on it again’, the man cut in, ‘For this is the last.’

He waited for a reaction. Then he continued,

‘We’re from Craigmore and she goes past the door. When she goes, we’ll have nothing.’

His wife was in the spirit for reminiscence.

‘I could cry this night. I am on this last run, and I well mind being on the first. I was a wee girl sitting on my father’s knee.’

I sought for suitable words of reassurance.

‘Sure they’ll likely give you a bus?’

‘They likely will. But they’ll have to give us a road first!’

Her husband concurred. ‘There’s forty or fifty families up in Craigmore and now we’re nowhere. Don’t know what’ll come of us.’

Two more men, John Meeks and William Barr boarded. The conductor, Tommy Anderson joined our group. Someone recognised the young chap as a Master Johnson. Of the newcomers, Davy Burns was the most expansive.

‘Ah mind when the fare to Newry was only tuppence. That was before the Bessbrook ones all wore boots!’ he added, enigmatically.

‘There was good craic on the final tram from Newry at night. Everybody talking. If you opened yer mouth too wide you might get a clout of a half-pint bottle! If you complained of thirst, you might get offered an acid drop. The morning tram was even noisier. Full of girls going to the mill, and them all singing as like as not.’

He was enjoying himself.

They’d ask if you liked it.

‘You’re not good,’ I’d say, ‘but give us another verse anyway’.

Off they’d go, laughing and singing. Them was good times but now they’re gone. There’ll be no fun like that on the buses.’

The lights dimmed, indicating that the car was slowing to a stop.

‘End of the line’, the Conductor called to the Copelands. Was it said with irony, I wondered. Goodbyes and good lucks were exchanged. They had petitioned the Directors of the Mill for a reprieve but with little optimism.

At Millvale along the line, our last passenger, bar myself, Jack Cowan got off.

Tommy Anderson told me the story of the two Brook men one time approaching the tram.

‘Are you going on the tram?’ asked the first.

‘No’, replied the other, one Willie Bradley. ‘I’m in a hurry today. I’ll walk it!’

At the terminus, the foreman concurred.

‘It’s sad but it had to happen. She’s too slow,’ he added.

Sheltering from the icy wind, awaiting the return tram to Newry, I had time to reflect on the Bessbrook/Newry tram’s history. It had opened with a flourish just sixty three years before in September 1885 and only two years after the Irish Tramways Act that enabled its construction. Its primary purpose was the conduct to Newry Port of the products of the Bessbrook Spinning Mill and the carriage of raw materials in the opposite direction. Michael Faraday had only recently made his great electrical discoveries. It was less than four years since the world had had its first electric tramway. Electric traction with the third rail system was developed by Siemens and Halske and shown at the Berlin Exhibition of 1879.

It was expected the Bessbrook tram would haul 28,000 tons of product a year. An ingenious innovation was incorporated in the local system, the flangeless wheel and shoulder rail construction of Mr Henry Barcroft of the Glen in Newry. This enabled the wagons to be used on the rail or on road, as desired. This was a unique world development. Another advantage was the ability to carry passengers too. At its maximum the driving car carried a load of 56 tons and thirty four passengers at a speed of 12 m.p.h. A 56 H.P. turbine made at Belfast fed the two dynamos via the mid-rail system. Yet at all road crossings, primarily for safety reasons, an overhead wire was substituted for the rail conductor.

My reverie was interrupted by the conversation buzz arising from the queue at the corner of the Square, awaiting transport to Newry. This was a different crowd entirely from that whose camaraderie and bonhomie I had so recently shared. Modern youth, self-possessed and self-assured, dressed in nylon macs and slouch hats with fur-lined bootees, not the peaked caps, and shawls and aprons of my recent companions. There were boys with girlfriends, a soldier going back from leave, and a gang of nippers, long-trousered and becapped, movie bound to Newry. Up at the front, girls joked with the Conductor, and from the rear floated the strains of the current croon sensation – ‘How are things in Gloccamara?’ – not liltingly as Davy Burns might recall, but ‘swooningly crooned’ – you know what I mean!

And so I ended my journey on the last tram to Newry. The Brook ones would tell you it was the longest tram in the world, because the track looped at both termini. My lasting impression was sympathy with Willie Bradley’s complaint – maybe it was ‘too slow’.

All that’s left is the occasional patch of overgrown track, such as up Derrybeg lane or to the back of Clonmore on the Armagh Road.

Such is progress.

Housing in Newry Past

Northern Ireland’s post war housing stock was worse than that of any other part of the United Kingdom, despite having been spared the worst of the German blitz. Most houses had been built before the First World War and they were grossly inadequate in quantity as well as in quality.

History of Newry Workhouse: Wm Alexander Davis

No relief from poverty in Ireland existed before the 1840s, when 106 Poor…

Gerry Monaghan : Family

Mindful of its gloomy history, I have always regarded the quarry with thoughtful apprehension. Despite this, as an older boy I would go fishing for spricks (sticklebacks) in its clouded, enigmatic waters. The spricks were much bigger here and so more desirable.

Later as teenagers, filled with the wild daring of that capricious age, we actually swam there. We would climb down the rocks to a ledge just above water level. The ledge afforded space for our clothes and allowed us to bask when the sun shone. Sheltered as it was by the high surrounding rocks, it then became a sun trap. From this ledge we would manfully plunge into the water, mindless of its awesome depth. We would then splash about with the clamorous exuberance of youth, shouting lustily, amused by the repeating echoes from the rocks around. Yet despite our apparent dare-devil abandonment, the water’s deep menace lurked in our minds like a prowling shark. When a swimmer occasionally felt some unthinkable, aquatic abomination touch his foot, all dare-devil pretence vanished in a frenzied flurry of white water as the would-be Tarzan swam frantically, flailing the water, seeking the safety of the ledge.

History of Newry Workhouse : Part 1

NEWRY WORKHOUSE IN THE CONTEXT OF POOR RELIEF IN IRELAND AND ENGLAND By…

Gerry Monaghan Part 3

3. Radio Days

We lived, my parents, Edmund and I and baby Donal lived in a large rundown house on Bridge Street, owned by the McCartneys, who lived on the ground floor. We occupied the first floor, in what now would be called a flat.

1916 Shipping Disaster

The fateful year of 1916 will long be remembered in world history. The Great War – the war to end wars – exacted a terrible toll in young men’s lives, especially at the Somme in France where in one day alone, 1 July, 19,000 young British troops – many of them, indeed, Irish (no part of Ireland was free then), some from Ulster and many from other parts of Ireland – perished in a fruitless attempt to relieve the French.

Gerry Monaghan: The Start

My first memories are of my mother – of her softness and warmth, her expressive face always beautiful to me, of her endearing, coaxing voice whose slightest irritated inflection would cause me dismay. She would exhort Edmund my elder brother by a mere two years, to ‘look after that child! Don’t let him get his feet wet!’ as we went out to play together.

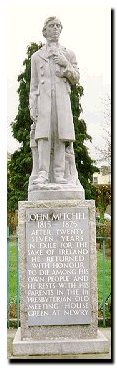

John Mitchel of Newry

John Mitchel (1815-1875) was a Young Irelander leader and perhaps the most esteemed…