Many of you attended John McCavitt’s ‘Flight of the Earls’ CD launch in the Arts Centre’s auditorium last evening for there was a packed house and indeed, extra temporary seating had to be installed. You were well entertained and informed and many availed of the opportunity to purchase the historical/musical CD. It will shortly be available in the shops but meanwhile it can be purchased from John through his great website (http://www.theflightoftheearls.net/) where too the following article (reproduced here by permission) can be browsed.

Trench warfare in the Gap of the North, 1600 in Cuisle na nGael (1987)

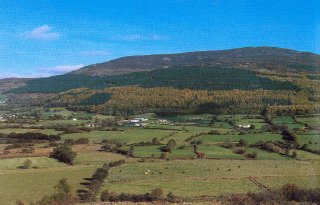

The perceptive modern-day traveller journeying South on a train from Newry to Dundalk has undoubtedly noticed the recently erected British military installations on both sides of the famous Gap of the North, or the Moyry Pass as it will be more generally called in this article. If one looks at the right hand side of the Pass in particular, one will observe that the defensive works there are both of the more recent, as well as of a much earlier genre. The old Moyry Castle in fact dates from 1601. Clearly though, even today the area in the proximity of the Gap of the North is of considerable strategic importance. How much more so was this the case at the turn of the seventeenth century is also worth noting. Indeed the events immediately preceding the erection of the Moyry Castle provide a fascinating insight into the power struggle between the Elizabethan English and the native Irish under Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone. By the year 1600 English efforts to bring the rebellious earl to heel had become successively unstuck. Moreover, many believe that at one crucial juncture, after the Irish had defeated the English so decisively at the Battle of the Yellow Ford in 1598, England’s grip on Ulster had become precarious to say the least.

In the aftermath of the Yellow Ford catastrophe, the English threw vast resources in men and money behind Essex’s expedition to Ireland in 1599 in an attempt to remedy the grievous situation. But this effort failed miserably too as Essex was to achieve little or nothing of note. Following Essex’s fruitless exertions, an exasperated Elizabeth turned to Lord Mountjoy, the general who was to eventually vanquish the hitherto unbeatable Earl of Tyrone. But Mountjoy’s ultimate victory was not to be achieved without one or two notable setbacks, none more so indeed than the battles at the Moyry Pass in the autumn of 1600. In the words of G.A. Hayes-McCoy, a military historian of the period, “Mountjoy’s early encounters with the Ulstermen were far from being glorious to the English arms”.2

Soon after assuming the viceroyalty, Mountjoy was to become persuaded of the utility of what may be described as a garrison policy. This was designed to affect a stranglehold on Tyrone’s northern power-base. The first demarche in this plan of action was reflected in the establishment of Sir Henry Docwra’s garrison at Derry in May 1600. At that time, in order to draw off Tyrone’s attentions from Docwra’s amphibious landing, Mountjoy made his first sortie through the infamous Moyry Pass. On this occasion his forces emerged relatively unscathed as O’Neill made little effort to intervene. The story was vastly different when Mountjoy set out from Dublin in the autumn of 1600 to travel through the Moyry on his way to Armagh. He intended to plant another garrison there as a further instalment in his policy of circumvallation. Faced with impending encirclement, Hugh O’Neill made a determined bid to frustrate the Deputy’s intentions. The northern earl let it be known that he would confront the Viceroy’s forces as they tried to traverse the Moyry and Mountjoy confidently rose to the challenge. The scene then was set for a major confrontation. It is against this background that the events in the Moyry Pass during September and October 1600 unfolded. But, before embarking on a narration and analysis of these incidents it would be wise to make it clear at the outset that the extant sources on which this account is based are almost exclusively provided by English army commanders of the time. Consequently they may well have been tinged with a tendentious nature.

Mountjoy had at his disposal on this expedition a force of some 2400 foot and 300 horse, while English estimates Tyrone’s strength as slightly greater. The Deputy arrived at Dundalk on the 14th September 1600. Shortly afterwards he encamped at the hill of Faughart, adjacent to the Moyry where Tyrone held fortified positions. Fynes Moryson, who was soon to become Mountjoy’s private secretary, recorded that the Lord Deputy resolved at the outset, “to march over him (O’Neill), if he stopped his way and make him know that his Kerne could not keep the fortification against the Queen’s forces”. But this was easier said than done, as Mountjoy soon found out to his cost both in terms of his own reputation and in the number of casualties his army sustained in the subsequent engagements. The Irish defences in the Pass itself consisted of specially constructed barricades and trenches made of a combination of stones, turf and palisades. Further up on the densely wooded Moyry hillside, the Irish had ‘plashed’ or intertwined the branches of trees together to form a further considerable impediment to the advancing English. All in all, the formidable nature of O’Neill’s defences astounded the Viceroy and his commanders. Mountjoy commented that in erecting such fortifications, ‘these barbarous people had far exceeded their custom and our expectation’.

The actual hostilities in the Pass raged on and off between the 20th September and the 8th of October 1600, at the end of which period Mountjoy retired, or should it be said retreated, with his forces to Castletown (Dundalk). Interludes in the fighting during this period were generally ascribed by contemporaries to torrential rainfall. Yet when fighting was possible, some ferocious engagements occurred between the two sides, with some extraordinary displays of valour being displayed by men from each army. The trial of strength began as soon as Mountjoy’s army pitched its camp at Faughart on the 20th September and a foraying party was sent into the Moyry to procure firewood and other necessities. This resulted in a two hour long skirmish. On the following day, hostilities resumed when a small party of some 20 ‘rebel’ cavalrymen rode to, ‘within a musket shot of our camp’. Evidently, this was too much for their English adversaries who seem to have taken this demonstration as a grave affront. About 8 English cavalrymen immediately set forth in hot pursuit and gave chase to the Irishmen who fled. Unfortunately for the impetuous Englishmen realization that they had been lured into a cunning trap came too late. One man was killed, while another was shot off his horse, having been struck in seven places. Luckily, as the English account of this incident goes, the badly injured man retained his presence of mind and ‘…feigning himself to be dead, suffered them without resistance to strip him of his apparel; by which means they struck not off his head, as their fashion is, but leaving him naked, within half an hour after he returned into our camp and being now very well recovered, is ready to requite their courtesy, when he shall find them at the like advantage’.

The next notable engagement occurred on the 25th of September, when under cover of ‘an exceeding great mist’, Mountjoy sent a detachment to test the strength of the Irish trenched. Obviously, the Deputy was proceeding cautiously, preferring to gauge the type of resistance which a full scale assault on the Pass might receive. Favoured by the element of surprise, the initial stages of this operation went well for the English. Things soured as they retreated however, and the foray resulted with some 12 men killed and 30 wounded on the English side. Ironically, an English account of this action comments of these losses that ‘the greatest part of which harm (as is guessed) we received from ourselves, the grossness of the mist disabling us to distinguish friends from foes’. It was at this stage that the apparently extraordinary inclement weather, even by Irish standards, intervened, causing a lull in the fighting for about five or six days. During this time even Lord Deputy Mountjoy’s tent was blown down.

When the hostilities eventually resumed, they proceeded with a vengeance, as on the 2nd of October the fiercest engagement of all was fought out in the Pass. Apparently the Irish were slighted by the earlier English tactic of attacking under cover of mist. Consequently, when the weather cleared by the 2nd of October the Irish began to taunt their English opponents. According to an English chronicler, they ‘reviled our men, as their manner is, calling them cowards for stealing on them in the mist, and asking why they came not again to the trenches, where they should find them better provided to receive them’ . In the midst of the ferocious engagements which then ensued, Mountjoy had a close shave with death as he made his way with his entourage onto a hill to observe the battle. In the process of doing so, one of the gentlemen who was riding ‘hard by’ him was mortally wounded. The Deputy’s good fortune in escaping death or serious injury was also shared by some of his officers. In particular, Sir William Godolphin, in leading a cavalry charge during the battle, ‘had his horse stricken under him stark dead with a blow on the forehead, that the blood sparkled into his face and some of the powder shot’. Others, however, were not so lucky. The English admitted that at least 55 of their men were killed in the engagement and that some 105 were wounded. At the same time they claimed that up to 400 Irish also died. It must be said that there is no independent verification for this estimation of Irish casualties and consequently a degree of exaggeration may be suspected. On the other hand, that losses were high on both sides may be accepted due to the fact that it was generally agreed by the English soldiers who took part in that day’s combat that it was, ‘the greatest made since the beginning of these wars’.

The engagements on the Moyry Pass reached their climax on that day and over the next few days they gradually petered out. One English commentator reveals the despondency which had by this time undoubtedly begun to pervade through the ranks of the English army. After the events of the 2nd of October, Sir Robert Lovell, writing to the Earl of Essex, commented on the ostensibly confident mood in the English camp but made no secret of the fact of his own feelings of doubt. “There is no talk but of passing the Moyerie, or lying in the mire, which I think rather; but for myself I doubt not to live and see your lordship as happy as ever you were”. Unfortunately for Lovell, his premonition of imminent death was to be fulfilled sooner than even he might have thought as he was killed later on the same day that he penned this missive. By the 8th of October, Mountjoy and his English army had had enough and they retreated to Dundalk. In the words of one of Mountjoy’s biographers, this ‘was a tacit but definite admission of defeat on the part of the English’. O’Neill’s response to this move was to withdraw his own forces from the Moyry Pass also. Hayes-McCoy attributes this decision by the Earl of Tyrone to a combination of different factors. In the main he believes that O’Neill was engaged in cunning politicking. “It was quite consistent with his conduct of the war to give the appearance of being determined to fight to the finish and then suddenly to cease fire”. Undoubtedly, this may have been a leading consideration, especially once Mountjoy had withdrawn from the Pass. But another explanation, not necessarily incompatible with this one may be just as feasible.

It is arguable indeed that Tyrone was not really interested in persistently preventing the English from advancing upon him through the Gap of the North. He well knew that it was just as practicable for the English to come via Carlingford, or to come by sea via Carrickfergus. Alternatively, further amphibious landings could be made such as that which had just been successfully negotiated at Derry. Rather the testimony of the strength of O’Neill’s preparations at the Moyry at this particular time and the dogged Irish defence of the Pass, which even many of the English commanders at the time acknowledged, may suggest that the Earl was after something more grandiose. It is possible that O’Neill was playing for higher stakes and that what he really wanted at this juncture was to inflict another defeat on the English of the dimensions of that at the Yellow Ford in 1598. Certainly, this was not beyond the realms of possibility because the Moyry Pass offered some of the finest natural advantages to the defending Irish army. Significantly, the historian Lord Hamilton has noted that Tyrone employed similar tactics at the Moyry to those which he had earlier used with such devastating success at the Yellow Ford. On that occasion also he constructed trenches to oppose the advancing English, though his defences on the Moyry seem to have been more elaborate.

Mountjoy’s reflections on the perils of traversing the Gap of the North at this time are important because they allude to the fact that he suspected what Tyrone may have been aiming at and wisely decided against hazarding his army. During the Moyry engagements, the Deputy said of the Pass that he was determined ‘to make this way a secure gate and passage to beat this proud rebel out of the North, which is such a stumbling block to the army, whensoever it shall pass, that it is a great grace of God, if at one time or another the army be not lost, and consequently the Kingdom; but at least both, every time we shall do anything in the North, will be desperately ventured.’ In other words, the Viceroy was alive to the possibly disastrous consequences of a serious defeat at the Moyry. What is beyond doubt is that Mountjoy’s tactics during the hostilities in the Pass were characterized by judicious, and as it turned out, well-warranted caution. His operations at that time were largely confined to a series of probes, never once did he try to bludgeon his way through with all his forces as well as his bag and baggage. Instead after meeting such stiff resistance he sensibly withdrew to Castletown to take stock of the situation. Consequently, for O’Neill there was little advantage to be gained by remaining in the Moyry once Mountjoy had declined to run his gauntlet.

O’Neill’s withdrawal from the Pass enabled the Deputy to consider again attaining the objective which he had originally set himself on embarking from Dublin, the establishment of a garrison at Armagh. It must be remembered that much was expected of Mountjoy by his superiors in England and that having promised that he would establish a garrison so close to the heart of O’Neill’s powerbase, then he was more or less obliged to achieve this declared goal. As a result, despite obvious misgivings about having to leave the Moyry unfortified when he passed through it unhindered later in October 1600, the exigencies of time and the necessity to realise his Armagh objective left him with no choice. Instead, he had to content himself with obliterating O’Neill’s trenches on the Moyry and cutting down much of the forestry in the area which provided such additional hazard.

As it transpired however the Deputy was also subsequently forced to temporarily abandon his aspirations in regard to Armagh. This must have come as a source of bitter disappointment to him. Inclement weather and lack of supplies were blamed for this setback. Mountjoy’s only consolation may have been derived from the fact that he managed to establish a garrison at Mountnorris. At least then, Tyrone’s defence of the Moyry had frustrated the Viceroy’s more ambitious plans. Moreover, in making his return journey from the North, Mountjoy was constrained into making an embarrassing detour via Carlingford to avoid passing through the Moyry, where O’Neill had once again re-established himself. Instead, the English army’s homeward journey took it back via Newry and then towards Warrenpoint. On reaching the Narrow Water, the English troops were ferried to the Fathom side and from there marched on towards Carlingford. These manoeuvres by no means went unopposed by O’Neill’s forces but at least they were not subject to the same perils that a return journey through the Gap of the North would have entailed.

In the short term, it seems a fair assumption that O’Neill had the upper hand on Mountjoy during the Lord Deputy’s venture into Ulster which began in September 1600. 0f course, in many ways this is hardly surprising given that it was often quite literally an uphill struggle for the English who were also at the grave disadvantage of having to assault heavily fortified positions. As one English officer explained, when they launched attacks on the Irish trenches, ‘we had only their heads for our marks they our whole bodies for their butt’. Nevertheless, it remains true that despite the initial braggadocio of the English officers involved in the Moyry operations at this time, Mountjoy’s army failed to break through the Pass and it was his army which first broke off the engagements by retreating to Castletown. What is more the Deputy suffered the further indignity of failing to achieve his objective of planting a garrison at Armagh. He then had to rather ignominiously take the circuitous route homewards via Carlingford. All in all, Mountjoy lost at least 200 dead and 400 wounded during his operations in Ulster at this time. But there were compensatory factors for the English. If it seemed that all the short-term advantages lay with O’Neill, there was also another side to the story which illustrated less auspicious omens for the Irish. After all, Mountjoy had preserved his army by wisely avoiding the risk involved in a foolhardy attempt to traverse the Moyry when the Irish defences there were plainly very strong. Almost concurrently with the Moyry engagements the first fruits of the establishment of Docwra’s outflanking position at Derry were reaped when the formidable Niall Garbh O’Donnell defected with his forces to the English there. Then, when the Deputy returned to the Moyry Pass with his forces in June of the following year, 1601, he ensured that the important task of establishing a fortification there was seen to as a matter of priority.

Initially, it was intended that two defensive works should be established, though eventually only one was erected and it still stands there today. Of course, in modern times, as it was mentioned earlier, it is noticeable that the British army has built fortifications on both sides of the Gap of the North. One wonders, will they still be there in another 400 years time.