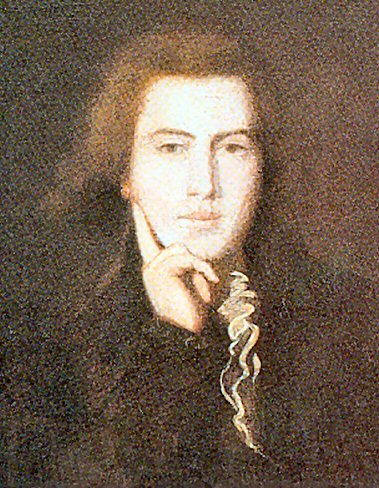

In the final decades of the eighteenth century the radical opposition in Ireland, inspired by both the American and the French revolutionaries of the time, was led in great part by Northern Presbyterians – among them the young poet and Belfast doctor William Drennan. For a few vital years in the final decade Drennan worked as a physician in Newry

where he led the United Irishmen and worked alongside and inspired such local leaders as Patrick O’Hanlon, solicitor, Tom Dunne, hedge-schoolmaster of Kilbroney and numerous radical merchants such as John Mercer.

Drennan became a main inspiration behind the United Irishmen, an idea he first mulled over in the years 1780-5. Like another Newry revoluntionary fifty years later (John Mitchel) William Drennan was the son of a minister. The Rev Thomas Drennan was minister of the First Presbyterian Church, Rosemary St, Belfast. As a medical student in Edinburgh William followed closely the course of the American War of Independence, knowing well that many of his Ulster Presbyterian forebears who had emigrated to the New World were intimately involved with it.

The radical cause was boosted by support from within the Volunteer movement which was recruited to defend Ireland against French invasion, while the British army units normally stationed in Ireland were fighting against American colonists. Many Volunteer leaders were Presbyterian merchants who suffered financially from restrictive trading practices. They petitioned for free trade, legislative independence, Parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation. The growing strength of the Volunteers caused the government to cede some reform in the areas of trading and legislative matters. Leaders like Drennan persisted.

By the summer of 1785 William Drennan was pressing for the formation of a secret, radical society to replace Dublin‘s aristocratic Reform Club. It was not until October 1791 that his society was formed in Belfast.

The original aim of the Society of United Irishmen was reform of the Irish Parliament rather than republican separatism, though the latter ideal was espoused by a number, including William Drennan. Although middle-class Presbyterians provided the leadership and Presbyterian tenant farmers and labourers the rank-and-file, not all Presbyterians supported the United Irishmen. Drennan described the original movement as ‘constitutional conspiracy’.

It had at first been an open and legitimate organisation. After Britain went to war with revolutionary France in 1793, the government clamped down hard on all those espousing the ideals of the enemy country. In June 1794 Drennan was tried for seditious libel but was acquitted due to the eloquence of his attorney John Philpot Curran.

In May 1795 the United Irishmen met secretly in Belfast and adopted a new constitution. Driven underground it transformed itself into a clandestine revolutionary and military organisation.

The brutal disarming and repression of Ulster by General Lake from march 1797 onwards, and the hanging of William Orr of Farranshane – a substantial Co Antrim Presbyterian tenant farmer in October 1797, served only to increase the fervour and determination of many members of the United Irishmen. Drennan lauded the latter as a martyr in his poem, ‘The Wake of William Orr’. Indeed the cry, ‘Remember Orr!’ became a potent mobilising slogan for rebellion in 1798 in Antrim and Down.

Still, when rebellion came, Drennan’s role was merely that of an observer. All across Ulster- and especially in Newry – leaders had been betrayed by spies infiltrated into the movement by government.

The rebellion was ruthlessly suppressed and the populace terrorised into submission. Though none of the ideals – reform, free trade or Catholic emancipation – were realised, under the Act of Union that followed, most Presbyterians and other Protestants came to support the Union. The Irish parliament was abolished and representation at the Imperial Parliament reduced.

Unchallenged Westminster support for the landed gentry and especially for absentee landlords (who composed the greater fraction of ‘Irish’ members at Westminster) resulted in an ever-burgeoning burden upon a growing Irish Catholic peasant society. A succession of potato failures in the nineteenth century led almost inevitably to the Great Famine of the mid-century, to over a million deaths and to twice to three times that number forced into emigration in the succeeding century. Trade privileges were reserved to the larger island. Catholic emancipation was delayed for a further two generations.

Drennan did not abandon his radicalism. He continued all his life to support Catholic emancipation and to maintain an interest in parliamentary reform.

William Drennan was heavily involved in the foundation in 1814 0f the Belfast Academical Institution. Indeed his continued radicalism may have contributed to the government’s withdrawal of the Institution’s annual grant between 1817-1829.

Drennan died in Belfast on 3 February 1820. He was buried in Old Clifton Street Burial Ground. His coffin was carried by six poor Protestants and six poor Catholics.

… Presbyterians to America …