Short Stories

Trouble the Yanks Bring

Poem for a Farmer

This poem is written for Mrs. Margaret Dolan in memory of her late father, Thomas McCreesh (McGinnis) of Tullyogallaghan, Belleeks, Co. Armagh. It is submitted by Rosemary Dolan of Guestbook. Newry Journal is honoured to reproduce it here!

A great, a grand outstanding man,

Whose goal was ever high;

Who to whate’er he put his hand

Found not in vain the try.

He lab’red well and managed good

The land he did possess;

Few farmers of his neighborhood

Were more of a success.

His homestead, so well kept and neat,

Of care and taste spoke out;

It certainly was up-to-date,

None better thereabout.

At fair and market he was keen,

A master of retort;

But never from a spirit mean

Would he one’s feelings hurt.

His knowledge of livestock was wide,

No guesswork judge was he;

Time-tested methods were his guide,

And could not bettered be.

For miles around he was well known,

And held in high repute;

Upon this point there sure were none

Who’d venture to dispute.

By grand example and advice

He upheld honour’s way;

And pointed to the heavy price

Transgressors have to pay.

All those within his reach and care

Most ably did he lead;

Their erring ways he did not spare,

Nor aught to them concede.

To church and clergy always he

Full strictly did adhere;

He in them did Christ’s guidance see,

And felt his presence near.

Good hearted and responsive too,

He of times did befriend

Those neighbours who, he well, well knew

Life’s trial weights did bend.

The drawbacks of the times could not

His staunch persistence blight;

He still held on to goals he sought,

And kept an outlook bright.

Discipline with him carried weight,

He strongly did it stress;

The reason why, he’d tell you straight,

He knew its usefulness.

And so this man his whole life through

Improvements round him wrought;

His record fine accents the true,

The high aims to be sought.

He showed the faltering weak ones how

From struggle, strength to wrest;

How not to human frailty bow,

But live up to one’s best.

Railway Bar Characters

Christmas Eve 2003 in the Railway Bar saw the unravelling of a story which had puzzled Wilbur Lundy from the Meadow from many a year earlier.

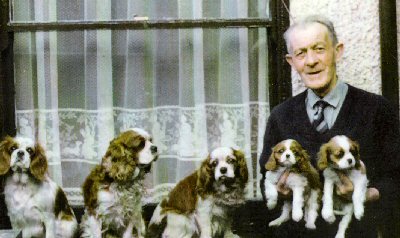

Myself and Liam Boyle were lucky enough to be present and witnessed the whole turning of events. Wilbur’s eldest son Billy was a keen dog lover and hunter [very much still is]. However the story dated back to the time when Bill was 11 years old – and was pieced together by the other two offspring of the Lundy household – Gerard and Robert plus information that Wilbur had unknowingly volunteered – what you are about to read, took years to unravel.

The Clink of Rhyme

A student here, from Ballintoy

A laughing fair-haired country boy

Felt now and then fit to employ

His Sunday leisure

In turning verses to enjoy

Poetic pleasure.

I showed him how with little cost

His thoughts were better far engrossed

In the blank verse of Robert Frost

And as a duck

Takes to the burn in which it’s tossed

He tried his luck.

The lines came supple, steady, clear

True to the country atmosphere.

There was no flowery discourse here

But honest phrasing;

And half a dozen times that year

He sought my praising.

But once he read his verses o’er

To some oul’ caillaigh at her door

Who had a name in three or four

Townlands for rhyming

That he might hear how much he’d score

By her skilled timing.

Awhile she listened to him, dumb

With not so much as haw or hum

Then, sucking at her toothless gum

She said, ‘I think

I’d rather hae the thochts that come

In lines that clink’.

By John Hewitt from ‘Loose Ends’ Blackstaff 1983.

I just LOVE this! The wonderful Brother Barney Liston taught us a love of poetry some 57 years ago at the Abbey Grammar (long before Hewitt wrote this!).

The young are reared on simple rhymes (nursery, to begin with) and doggerel – or trite pop lyrics. It takes time, tuition, practice and loving guidance to progress – in any enterprise.

I was initially dumb-founded that ‘prose’ – to me, i.e. non-rhyming poetry – could be counted in that exclusive company.

Hewitt, I suspect, is nodding in the direction of blank verse, but subliminally showing a personal preference for rhyme. He is also extolling his own roots (in the Ulster-Scots tradition) and his admiration for those who champion that – and local poetry – doggerel, if you like.

The cailliagh here (I think of our own Alice Kelly of Rostrevor – apologies Alice – I know you have your own teeth, and physically do not fit the bill – but you are an inspiration for the youthful budding poets amidst us!) ) is counter-arguing with the tutor, Hewitt. Like her, I prefer ‘lines that clink!’

I also like a laugh! This poem never fails to bring a smile to my wrinkled old face!

Ballad of William Bloat

Ballad of William Bloat

In a mean abode, on the Shankill Road

Lived a man named William Bloat

He had a wife, the curse of his life

Who continually ‘got his goat’

Till one day at dawn, with her nightdress on

He cut her bleedin’ throat!

With a razor gash, he settled her hash

Oh never was crime so quick

But the drip, drip, drip, on the pillowslip

Of her life blood – made him sick.

And the pool of gore, on the bedroom floor

Grew clotted and cold and thick.

And still he was glad he’d done what he had

When she lay there stiff and still

But a sudden awe of the vengeful law

Struck his heart with an icy chill.

So to finish the fun – so well begun

He resolved – himself, to kill.

He took the sheet from his wife’s coul’ feet

And twisted it to a rope

And he hanged himself, from the pantry shelf

‘Twas an easy end, let’s hope!

In the face of death – with his dying breath

He solemnly – cursed the Pope!

But the strangest turn to the whole concern

Is only just beginning

He went to Hell, but his wife got well

And she’s still alive – and sinning!

For the razor blade, was foreign made

But the sheet -was Belfast Linen.

[by Raymond Calvert]

My Father’s Son

The three Pats, Gibney, Lundy and Kavanagh were chatting over a pint in the Railway Bar one evening – oh, all right, they had a pint each – and having exhausted the usual topics of the shortcomings of women, the latest football results and the price of hay, they finally got round to telling each other riddles. There was a problem here, for none was too sure exactly what a riddle was. Anyway, Lundy, the intellectual, began with the Riddle of the Sphynx.

‘What is it’, he says, ‘that walks on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon and evening, but three at night?’

‘That doesn’t make any sense!’ snorted Gibney.

‘Sense or not, what’s the answer?’ the first went on.

Well, the other two wrinkled up their eyebrows in a pretence of thinking, but there was no way they’d ever come up with the right answer. In the end they just gave up.

‘It’s man!’ crowed Lundy, triumphantly. ‘Can’t you see? When he’s a baby, in the morning time of his life, he crawls on all fours. Then as a man, he walks upright. When he’s old, he needs a walking stick.’

‘Well, I hope yours makes more sense,‘ jeered Kavanagh, though, if truth be told, he was racking his brains to think of one when it’ud be his turn!

‘A house with neither windows nor doors, but golden treasure it holds within,‘ chanted Gibney, forgetting the rhyme but getting the gist of it just the same.

‘Now you’re just being silly! How cud there be a house with no windies or durs?’

‘You don’t know, is that what yer’re saying?’

‘What’s the answer yer’re lukkin’ for?‘ says the other.

‘The right answer, of course, ye hoor ye!’

They were bate, ye cud see. But they wudn’t own up. In the end, Gibney too had to explain.

‘It’s an egg. Isn’t it home to the chicken before she hatches? And it has no windies or durs. She has to break out. The yolk is the treasure!’

‘Here,’ says Pat, suddenly brightening, ‘which should ye say, ‘the yolk of the egg is white’ or ‘the yolk of the egg are white’?’

‘Eggs’ yolks ‘s yellar!’ shouted Lundy. ‘And I hope you don’t think you’re getting off that aesy!’

But Kavanagh had had a brainwave. He’d heard one weeks before from a man in a pub in Kerry, when a young lad had entered. He had said,

‘Brothers and sisters have I none, but this boy’s father is my father’s son’.

‘Yer talking in conundrums’, complained Paddy Lundy. He might have been for all he knew, but he stuck to his task.

‘All right, I’ll say it again for yous, ‘Brothers and sisters have I none, but this boy’s father is my father’s son”.

‘Aye, it’s a good one,‘ says Gibney. ‘Is it your round?’

‘Don’t try and change the subject. What’s the answer?’

‘There’s no question that calls for an answer!’ roared Lundy.

‘The answer to the riddle!’ he persisted.

‘What is it you want to know? Who’s the brother or sister, the grandfather, the father, the son or the Holy Ghost?’

‘Just give the answer,’ says Kavanagh, weakening, for he wasn’t sure himself.

They didn’t want to admit defeat. But there was nothing they could even guess. In the end, Kavanagh took pity on them and said,

‘Luk, yus wouldn’t know him anyway, for it’s this fella I met when I was on holiday in Kerry!’

[In case you are beating your brains out too, the ‘boy’ is the son of the speaker, so the boy’s father is the speaker: when he says ‘my father’s son’ he is referring to himself as that son, and obviously the second father is the first ‘boy’s’ grandfather. I hope that’s clear now!]

Round Square

‘She needs a square of being round!’ – she’s intellectually-challenged: she has a wee want in her: she was behind the door when brains were being given out etc.

But the expression reminds me of a story of my first job, many decades ago. It was the custom then – it may well be yet – to ‘take a hand out of’ every new recruit. You know the kind: Get me a new bubble for my spirit level.. a new knot for my tie etc.

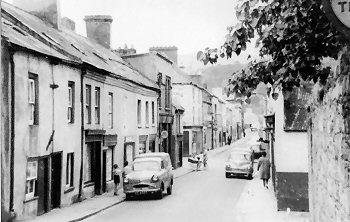

I worked in Thompson’s Cellars where the Pound Shop is today [Credit Union until recently]; we packed orders for licensed premises across the province. Henry Thompson’s and Quinn’s the Milestone [Protestant and Catholic firms respectively] had amalgamated. Our delivery drivers included Oliver McCaul – from Orior Road, and Jim Parks, then of High Street. We’d have to check our schedule as we did our rounds: if we were in a Unionist area, we announced ourselves as Henry Thompson’s, if Nationalist, as John Quinn’s! Where it was ‘safe’ [for us that meant the latter areas] the driver might make a fool of his new helper by ordering him into the premises first, to request ‘a long stand’ with which to help empty the van’s contents.

I was a bit ‘green’ and was certainly fooled the first time – being told to wait a while until the proprietor concluded the numerous chores that were apparently busying him. When I cottoned on, I also realized that the ‘long stand’ was in fact doing me no harm at all, so I stretched it out, and joined in heartily in the laughter which followed at my expense!

There were certain generous proprietors who had no problem about putting up ‘a bit of grub’ or even an odd pint. [There was certainly no fuss made then, forty years ago, about a driver having one only.] But you had to ‘know your man’. You usually timed your deliveries to ensure that lunch-time [anytime between twelve and two] coincided with your arrival at one such owner’s friendly door.

‘Go on in first there, lad, and ask for a ’round square’ to help us with this drop.’

‘You sure? A round square? Doesn’t sound right!’

‘None of yer cheek! Do what yer told, and be quick about it!’

I obeyed.

‘John Quinn’s delivery. The driver said, if you don’t mind and as it’s lunchtime, could he and I have the usual round. He’s in the bookies but he’ll be along in a minute. If that’s all right, that is!’

‘Cheeky get! Which driver is it today?’

‘Mr McCaul. If it’s all right with you, I’ll have today’s Special, with a large glass of iced milk! The driver will pay for it.’

‘Bit forward yerself, young lad, aren’t ye? Well all right, just this once!’

Five minute later, Oliver strolled in with a broad grin on his face.

‘Well, young lad, did you get the ’round square’?’

‘I ordered the round, all right. And I explained to the barman that you’d square him!’

After that, I got the respect I thought I deserved!

Berry Ballad

Come all yous loyal brethren, I hope yous will draw near

It’s of a cruel murder boys, as ever you did hear

A woeful lamentation I mean to let you know

I had to die for Chambre and I never struck a blow.

Francis Berry is my name and my age is twenty three

I am a Roman Catholic, was reared in Drumintee

I am my mother’s only son, the truth I’ll ne’er deny

I left her broken-hearted in the townland of Adavoyle.

It happened in the year of eighteen and fifty two

For little I knew of the dangers great, I had for to come through

At nine o’clock on Tuesday night, my house they did surround

And I was taken prisoner and handcuffed on the ground.

They marched me off to Newry town, for me they’d take no bail

I was sworn by that a’cursed Singleton and forced to Armagh jail

He swore that I presented, a pistol and a ball

And God he is my witness, on Him I now will call.

I never fired at any man, God witness to the same

It’s in yer blood, cursed Chambre but, my hands I ne’er did stain

And God will say to Chambre, upon his dying day

Depart from me cursed Chambre, you did my child betray.

Depart from me Chambre, you caused his wounds to bleed,

Depart from me cursed Chambre, to thee I’ll give no heed

On the day of my execution, it was a shocking sight

To see the trembling victim, as he was dressed in white.

And standing in the jailhouse door, to view the gallows tree

It put me in mind of our Saviour who died on Mount Calvary

And standing on that woeful trap, praying to God on high

For to have mercy on my soul, for innocent I must die.

Come all my loyal brethren, my race is nearly run

And I will be an angel bright unto Thy Kingdom come

I’ll be governed by one clergy, its church is on a rock

Christ is our foundation and St Peter guides his flock.

Here’s to my loyal mother, I send these locks of hair

And also to my sister, in hopes that she’ll get care

And in Killeavy Churchyard, my body will remain

And against the Day of Judgement, I’ll see yous all again.