Playing there as young boys we used to marvel at how deep the water was in this Mill Race: and with the aid of a stick cut from one of the many trees and bushes…

Places

Meadow: Derrybeg Drive

Those of us lucky enough to grow up in The Meadow of the 50s and 60s had a number of McCrums as pals – I remember with fondness the late Eamon, with whom we’d play football in the Big Green – then there were Terry and Liam who were of an age with us, class-mates and pals, and there is Martin (altar-boy in St Bridgets) and Finnoula.

The Canal and Towpath

To the people who lived in the

Within a short walk from their front door the canal towpath enabled them to take a leisurely stroll out into the countryside. To parents it was somewhere to take their children for a walk on a sunny afternoon, and to the children themselves the canal and its associated towpath was an adventure playground, albeit an out-of-bounds one to some of the younger, unaccompanied kids.

The good folk of the Square always looked upon the towpath as their own special domain. This mindset was probably brought about by the fact that

To some of the people who lived in Linenhall Square (The Barracks) a generation before me – that is, those folks who lived there during the Second World War – the canal towpath was their escape route following the sounding of an air raid imminent-warning siren. It was the considered opinion of those persons that during an air raid it would be a lot safer to be out in the countryside and away from any built-up area.

This particular belief was made more poignant following the horrific air raids on Belfast in April and May 1941, and also following the alleged radio broadcast by William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw) that the Luftwaffe might bomb Lindsay Hill (well, at least knew how many steps there were up to St Clare’s Avenue!).

The unfortunate truth of the matter is that free-falling bombs released from aircraft travelling at speed on a dark night are not the most accurate of weapons; so therefore the people who favoured exodus from the Square, to Brady’s field, would most probably have found it a lot safer and more comfortable to endure the claustrophobic confines of the Linenhall Square Air Raid Shelters. Fortunately this was never put to the test as Newry escaped the war free from aerial attack.

…. the weir …

Jerretspass: concluded

After the war things got very bad. There was no work and less money so eventually Tom Burns and I decided to go to

Irene Dean’s first wage

At the age of fourteen and the eldest of five children I was excited at starting my first job in Dromalane Mill.

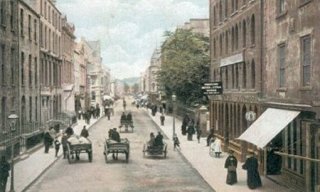

Monaghan Street of Old

Marie grew up at 45 Monaghan Street, next door to Garvey’s Eating House. She remembers number 43 was always packed on Mondays (fair days) and Thursdays (market days).

She herself was the only girl of her family. She had five brothers, including the late Adrian (Aidan), husband of Brenda of The Gardens, Bessbrook: Pat, who sharpened saws and knives (Stephen Downey remembers he sharpened his butcher’s knives and saws); Pat married and lived in Orior Road with his children Raymond, Joyce and Emily: Kevin, who settled in Australia [his wife died in Australia in August 1994] and their son, Eamon: and Seamus. The fifth brother Eamon married in the USA and reared a family of six children. Their parents John and Emma D’Arcy were married in 1921. Emma’s father (and Marie’s grandfather) was called Kavanagh and was also from Monaghan Street.

Marie used to collect “skins” door-to-door for Mrs Garvey, to help feed the pigs she kept for bacon etc. for her eating house. She recalls carrying two buckets full of these slops down the length of Monaghan Street to feed these pigs. Sonny McCullagh, her next door neighbour, would often help her. The buckets didn’t half pong. In those times (and long after too) people used to rear pigs in their back garden for a source of income. Garvey’s pigs were kept in a shed on waste land behind Hollywood’s garage at the top end of Monaghan Street. Many people remember witnessing the (public) slaughter of these animals when the investment had to be realized. Apparently the squeals of the pigs when they realized their imminent fate were indeed harrowing! The “skins” collected consisted of household vegetable matter (potato skins, carrot, cabbage leaves, dinner plate scrapings etc.) which householders separated and stored for the purpose. Contrary to regulations, some residents in the new housing estates of the 60s kept a pig in the back garden and fed it thus. As teenagers we used to scoff our friends by publicly and loudly demanding that they call soon to collect the “skins” which were rotting and smelling in storage. It was a ruse if repeated when your pal was chatting up a girl, was guaranteed to turn her off him! Marie recalls the residents of Monaghan Street then, as follows.

MONAGHAN STREET, NEWRY IN THE 1940’s

The D’Arcys lived in number 45 Monaghan Street (odd numbers only on that side of the street) but Marie’s folks had lived earlier further along, at number 57, where Hugh McKenna until recent years has his off-licence (The Cork and Bottle). Marie was born there!

Number 41 (beside the railway line and in front of Willis’) was owned by a Mrs Collins. Her husband was a sea-captain and wasn’t often there. Although they owned the first four houses of that block (the others paid rent to them) they did not own a radio. Marie remembers during the war, when news was eagerly sought, Bridget Garvey, next door, would turn up the radio in her front room. All the neighbours would sit on the windowsill outside and listen attentively. These four houses were later sold to Frank Murphy of Pound Road.

At 47 lived Charlie Rodgers. He was married to Cissie and they had children Phyllis and Joe. Charlie was a brother of Petie, who like him grew up across the road, next door to Gorman’s, the hairdressers. Petie, until his recent death, resided in Kiln Street. Number 49 was originally used as a store for the shop at 55 (see below). At 51 was the office of Willis’ bakery. Although it was not a shop, Marie remembers getting delicious fresh buns there. At 53 lived the bakery manager. He was able to get to work through his back-yard.

Number 55 was a shop, a general store. It was called Robinsons. Marie remembers a clutter of jars etc. on the stone floor. The family was Plymouth Brethren. Meetings were held in a store that was located between McMahons and the shop. Later Tommy and Belle (Isabel) Crawley took this shop and lived at the back of it. Their children were Mary, Noreen, Pauline, Kathleen, Thomas, Pat and Benny (who once had the shop in Stream Street.) Pat is bursar of Abbey Grammar School, Courtenay Hill.

As mentioned number 57 was Kavanaghs, Marie’s people’s house. Marie’s mother’s cousin Paddy Kavanagh lived there then. His children were Tony, Carmel, Joseph and Arthur. Later they would live at Ballinlare Gardens, in Killeavey Road, the Meadow. They were relatives of Joe of Derrybeg Drive. Marie’s mother Emma had died in 1932 of tuberculosis. Like the word cancer today, many people then would not speak the disease’s name, for it carried away so many of the poor. John (Marie’s father) remembered that some people would not even enter the house where she had died of it. There were just two bedrooms. Overcrowding and poor diet/conditions contributed to the spread of the disease. Today T.B. is making a big comeback. There are 300 new cases per year in Ireland. Now there are over 4 million sufferers worldwide. It is especially rampant in developing countries where there is little availability of the antibiotics used to counter it.

At 59 lived the McConaghy’s. Today their grandson Declan works for BBC’s Radio Ulster.

At 61 lived the McCormacks. Charlie worked in McCanns. Children of this family included Philomena who would later marry John Duffy. Phyl died a few years ago and is sorely missed by her loving husband and family.

Other McCormacks were Kathleen and Billy. Billy was a staunch trade union man. He became involved in the labour split of the forties in Newry that centred on the Queen Street Union Hall. Jimmy Kavanagh (Mollie’s brother) was on the same side with him. Tom Kelly was on the opposing side.

At 63 lived Mr and Mrs McGuigan. Eileen McGuigan was their grand daughter but was reared as a daughter. Her mother was Rose. She went to the United States and married a man named Murphy. Rose was a real good-looker. She worked in Moloccas ice-cream parlour in Warrenpoint. Josie Rafferty, Marie tells me, was from John Martin Gardens. She was related to Dr (Ronald) Rafferty.

Maurice Rowe (Marie’s husband) remembers about Garvey’s eating house, that you would always get a good hearty meal there. He recalls the men from Crossmaglen and from Mullaghbawn, who would sit outside, on the windowsill, eating their meal. There’d be two rough tables there for them. The atmosphere was totally friendly and relaxed.

At 65 lived Mickey Flanagan and his wife. They had no family. He was a brother of Mrs McGuigan who lived next door.

Other residents of the street included the Treanors, at 67. They were three sisters, one a dressmaker, Minnie from Dundalk. At 69 lived the Mulhollands. Johnny Mulholland’s daughter Marie lives in Loughview Park and Pearse and Oderin are well known. Johnny’s father worked on the railway. His other children included Jimmy, Lily and Chrissie. He and his wife also reared Dessie Kavanagh, who was a nephew of old Mulholland’s wife.

Number 71 (today Pat Duffy’s shoe shop) was an empty shop belonging to a Flanagan who lived further up the street. In the blackberry season it was used for collecting and processing the fruit, as Gavagans of Francis Street would be in a later generation. Upstairs here lived a Belfast evacuee, one Jackie Hearst, an old and well-loved character about Newry who was one of the most accomplished accordion players ever heard. He achieved some little fame, playing in several bands, including one bearing his name but never achieved the recognition he deserved. With him lived his mother, his sister Evelyn and his niece Agnes Storey. She later married Brendan Macken of O’Neill Avenue, father of the late Paul who used to participate in quizzes.

At 73 lived Bridie and Peader O’Hare and their children David, Pierce and Jeffery. At 75 lived a very short man named Mackin who worked with enormous shire horses for McCanns. He had two daughters Mary and Rosie. At 79 lived Mr and Mrs McCourt (even shorter!) who were a quiet and unassuming couple with no family. Next door at 77 were the Gouldings with their children Pat and Brian.

Number 83 housed the Gunns who owned a pub there. The man’s wife was a district nurse. Later they lived in the Glen. Philip, their son, married and emigrated to Brazil. On the other side of the street, beside Gormans (36) and Rodgers (38) lived the Bradys (40). They were cattle dealers. There were three sons Jim, Harry and Pat. There were also three daughters, Nellie, Mollie and Dora. Much later Jim Brady with his wife and family lived in the Meadow. At 42 were the Hillens, who were grocers (where Rices is today). Mary and Pat McParland lived at 44. He worked in O’Hagans. Mr McParland, retired vice-principal of St Paul’s School Bessbrook grew up here. At 46 lived the Dohertys. There were four sisters. One was a friend of Dolly Garvey. Her name was Bridget . There was also one brother.

At 48 was the McAteers. Peter was a taxi driver, his wife a dressmaker. They came to live here in the late 1950’s. They were not overfriendly. Their children Rita and Peter were twins. He was ginger haired. He worked in the gas-works.

There was a garage at number 50. It was often used as a coal store. During the war German prisoners of war were kept there and made to work, guarded by British soldiers. Amongst other things they fashioned children’s toys from wood.

Beyond this was Barney Hughes’ pub, favourite watering hole of the men of the area, and now Gerard McGuigans. Marie also referred to one Frank Quinn (known as Pipe) who worked as a foreman in McGowans printers. He was a stylish man who dressed well. He died in his eighties in 1995.

War Memories

A Newry friend recently received the following e-mail from an American soldier who was temporarily billeted here in the War.

“I was in the US military. My stay in Newry was from December 1943 to January 1944. Our barrack was a large two-story building next to the local Creamery. Your grandmother, then a girl in her early twenties living in her mother-in-law’s home which was also a restaurant just across the street from us, must often have served us meals.

I still wonder at the beauty of your countryside. Newry was an inland port. Before I was aware of this I had a scary experience. This was of ships sailing majestically across lush meadows. From a distance I could not see the waterway which carried these craft.

We became acquainted with some small children of 8-10 years of age. I don’t know if they were your forebears. Anyway we were told that if we could supply the sugar, their older sister would bake an apple pie for us. That evening eight of us spread ourselves around different tables in the mess hall. We emptied the sugar bowls into a container to hand. The sugar was delivered and the following day a huge pan of apple pie arrived for us. It was a kind of hard way to go about it, but the pie was delicious.

We were then sent to Lampeter for further training prior to the invasion of France. I was on Omaha beach and that was a real scary experience.

Thanks for responding. Hopefully I may still be lucky enough to return to Newry. I am now 77 years of age and time is passing fast. Cheers to you and your family.

Calvin Puckett.”

I may add that my own grandmother remembered a GI come to her eating house requesting food. She explained that her rations were out and she had no flour to bake bread.

“You need flour? I’ll get you flour, you bake me a loaf.”

Within minutes he returned with a whole sackful. She baked the bread.

He was caught and punished.

I would love to hear more tales of the American GI’s in Newry of that time. Please e-mail your stories to us.

Back of the Dam

Gerry Monaghan’s memories:10

Gerry Monaghan’s Memories 10

Mindful of its gloomy history, I have always regarded the quarry with thoughtful apprehension. Despite this, as an older boy I would go fishing for spricks (sticklebacks) in its clouded, enigmatic waters. The spricks were much bigger here and so more desirable. Later as teenagers, filled with the wild daring of that capricious age, we actually swam there. We would climb down the rocks to a ledge just above water level. The ledge afforded space for our clothes and allowed us to bask when the sun shone. Sheltered as it was by the high surrounding rocks, it then became a sun trap. From this ledge we would manfully plunge into the water, mindless of its awesome depth. We would then splash about with the clamorous exuberance of youth, shouting lustily, amused by the repeating echoes from the rocks around. Yet despite our apparent dare-devil abandonment, the water’s deep menace lurked in our minds like a prowling shark. When a swimmer occasionally felt some unthinkable, aquatic abomination touch his foot, all dare-devil pretence vanished in a frenzied flurry of white water as the would-be Tarzan swam frantically, flailing the water, seeking the safety of the ledge.

There were a half dozen disused granite quarries in this area and we had swum in several. Most, at some time or another had claimed the lives of boys. But my narrative has jumped ahead of its time. In the interests of clarity I will return to the year the war began.

First a word about my brothers and how we related to one another. Edmund was the eldest. He was then about ten years old. He and I had always been coupled, our names linked. Edmund had always had a special relationship with mother, perhaps because he was her first. She spent more time in conversation with him than with any one else. She also demanded more of him, expecting him to shoulder more responsibility. She was always quicker to blame him if anything went wrong with the boys outside. He was responsible, and generous with the rest of us, but could be forceful – not so much with me as with our other brothers.

Donal, two years younger than me, soon outgrew me. He was ebullient and big for his age, but soft. My aunt Alice used to say, ‘He’ll be a big policeman when he grows up.’ Curiously Donal had never become linked with another brother, as Edmund and I, or Gerry, or Brian and Dermot. I guess this was because Brian, his immediate subordinate (age-wise) and natural link was, like Donal himself, extremely independent and single-minded. Therefore the two could never mesh.

Edmund and I used to annoy Donal, who was tall for his age and very thin, as we undressed for bed. Using our fingers and making the appropriate sounds we would pretend to strum his ribs, harp-like. Of course he resented this and would pull away complaining to our mother. She would not allow sibling mockery but would often be too busy to prevent it entirely. Despite – or perhaps because of – the leg-pulling he sometimes suffered, Donal became very resourceful and ambitious and unlike the rest of us, very astute in the commercial sense.

We were all usually put to bed at nine. The younger boys occupied the double bed in the large back room while Edmund and I slept in the small back room. Sometimes just for mischief after we retired, we would decide to frighten the younger lads. One – usually Edmund- would sneak into our parents’ bedroom before they retired. In the wardrobe my mother had an old fur coat which suited our purposes admirably. Shrouded in this frightening bear-like disguise Edmund would creep towards the bedroom door of our innocent, unsuspecting younger brothers. The door would creak as he slowly pushed it open. Then moaning barely audibly he would slowly slither towards the bed. Of course they suspected it was us but boyish imagination often overcomes mere logic and they were also inhibited by the puerile pride that boys have in never showing fear. Imagination aided by the shades of night is fertile ground for fear. Their nerves would finally break, pride would be ripped away by the dark claws of terror, the gloom would be rent with their unnerved, quavering voices crying, ‘Mammy, these fellas are scaring us.’ This would be hilarious to Edmund and me. We could hardly contain our stifled mirth. Hearing the commotion, mother would come to the bottom of the stairs.

Speaking slowly and quietly in a firm voice loaded with threat, she would say, ‘If I have to come up these stairs you will both be sorry. Don’t let me hear another sound.’ At this she would return to the living-room closing the door quietly behind her. We knew that she knew who was at fault and that was enough. We knew she meant every word and we stopped our fooling at once. Lions and tigers are undoubtedly frightening beasts but they are far away. Mother was close and when aroused, every bit as fearsome.

With four energetic and often fractious boys and a young child, mother had her hands full. While father was at work she was busy with the cooking, cleaning and running the home. During the normal day we would all be at home only at meal times. The worst time for mother, her patience would be sorely tested. Sitting around the table waiting, with noisy banter, we wanted to eat to get out again quickly, oblivious of her labours. The older boys were always teasing the younger ones who would complain loudly. That would do it and mother’s reaction was fierce. With one hand on the loaf she would turn, her face like thunder, the bread knife poised in her other hand, and say, ‘If you do not behave yourself, I’ll give you a nick of this knife!’ This had an immediate sobering effect on the miscreant being addressed, and to us all. This small, volatile woman was not to be toyed with. We all knew that she was capable of anything. She might throw the knife, or a spoon, or anything that came to hand. She had done it before. Fortunately like most women she was no good at throwing things, not very accurate, so no one ever got a knife in the chest of in the back as he dived for the door. However it was a realistic hazard, and it concentrated our minds, causing us to moderate our thoughtless behaviour.

Father was usually absent at work, but even when he was there, it was mother who was the disciplinarian. As an indulged only son, father’s own relaxed upbringing ill-prepared him for his role as the head of a large family. He did not understand sibling rivalry or the devious machinations of juvenile politics. He seemed unaware of the acute perceptions of kids in spotting parental weakness and their unflagging persistence. Fuss and clamour overburdened his unworldly mind so that he would part with anything in the interests of peace.

Even as a toddler Edmund perceived dad’s weakness. On one occasion when mother had gone out to the shop and left father in charge, Edmund took advantage of mother’s absence by demanding of father, ‘Daddy, I want that clock!’ as he pointed, to dad’s dismay, to the clock on the mantelpiece.

In the year that the war began Donal was old enough to attend the convent school. As I was still at the same school I offered to take him. As the school was on the same street mother allowed this. Off we went hand in hand. When we reached the school a few minutes later I brought him directly to the babies’ class. It was on the ground floor, in the small enclosed yard beside the fire escape. Opening the classroom door, I pushed him firmly inside and, without a word, closed the door. I then went to my own class. So you see, Donal had been injected into the school rather than introduced. A few days later in the middle of the morning as mother went about her chores, to her surprise Donal came bouncing in unexpectedly from school. His brown eyes were dancing in his head as he exclaimed, ‘Mammy, I’ve bracted out! I’ve bracted out!’

Two years younger than Donal, Brian was then about three years old. Even at this young age his character and temperament could clearly be discerned. He was single-minded and stubborn, but quiet if left alone. If his animosity was aroused he could be quite intractable. Brian did not like fuss of any kind, especially if it was directed at him. If there was a family gathering or party that perhaps entailed taking photographs, Brian could become truculent , especially if he was put under pressure to submit or conform. He would howl belligerently and would not submit. Aunt Theresa often referred to him as the ‘Young Turk’. As a result, in family photos of this era, Brian is often depicted with his knuckles in his eyes, crying.

Because of these traits he was often left to his own devices, which pleased him. Always short on words, he was however very dependable.

Dermot was just a baby at this time. He is the only one whose birth I remember. All the others seemed to have always been there. I remember mother being confined in the house. There was lots of quiet, urgent babble. Then I remember going upstairs to the front room to see the new baby that my mother had received, I believed, from the doctor. She looked tired and wan, but she was there smiling with the baby at her side. Although I understood the baby to be new, it looked old and worn. Apart from curiosity, I cannot remember feeling any great tides of emotion at the time.