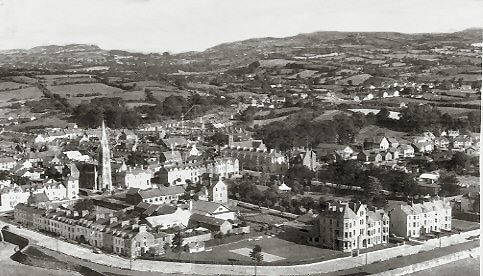

Forkhill today has become somewhat of a dormitory village with extensive new housing largely out of character with the village we so love. It retains its unique appeal however, and is an ideal site from which to explore the charms of South Armagh.

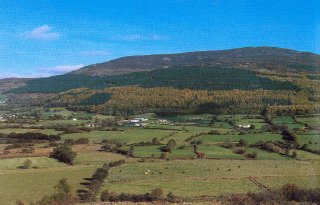

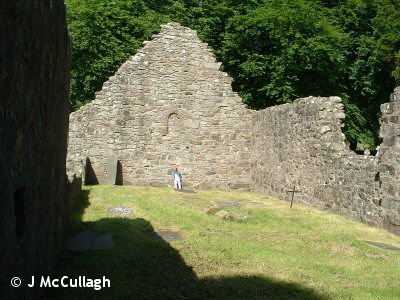

In the nineteenth century it was quite an industrial village with a corn mill, a scutch mill, a hotel, a post-office and several grocery and drapery shops. There was also a Petty Sessions Court once a month and frequent fairs. The surrounding countryside was sown in oats and flax and potatoes. In 1881 its population was 177. The main attraction then for tourists was a trout lake on Alexander’s estate which also had picnic sites. It sits at the western end of Slieve Gullion which dominates the skyline. Just outside town in the townland of Shean were the remains of an ancient priory. Urney Graveyard is a half a mile away.

Squire Richard Jackson (remembered in the beautiful song The Boys of Mullaghbawn, elsewhere quoted here) was the most renowned local landlord, highly thought of in life, though one clause in his will which clearly discriminated against the majority population caused untold hardship after his death.

Forkhill school under his bequest had a schoolmaster called Knowledge (a nickname, it is believed, deriving from his profession) who was willing to teach the local children their prayers in their native tongue. The Rector Rev Edward Hudson (1779-1795) removed him and replaced him with a teacher named Barclay who would ‘educate the children in the Established Church’ as the bequest had stipulated – teaching the ‘Established Church Prayers’ in English. Barclay had a brother-in-law, Dawson, who was Hudson’s bailiff and rent collector, and a spy and informer. On his word two local men were convicted of some crime, one named Bennett being transported and the other, Donnelly being subsequently hanged. Dawson was also the chief suspect when the parish priest’s home was broken into and his holy vestments shredded. Local anger boiled over.

A group of local Raparees set out in search of Dawson, but failing to find him attacked Barclay instead. Three members of one family were caught, tried and sentenced for this crime, one being executed. Local tradition has it that they were all innocent. English security presence in the area increased. On December 19th 1789 the Rev Hudson was himself shot at and the horse under him was killed. The whole area including nearby Mullaghbawn was active in the United Irishmen insurrection at the close of that century.

There are some among the older generation of Forkhill who still remember the mills operating. One was owned by a family called Brooks and one by a family named O’Neills.

Local farmers had their corn threshed by steam threshers in the field. It was then taken in sacks to the mill in Forkhill. It was crushed fine and made into pollard (crushed oats with nothing removed). This was a winter foodstuff for cattle. Farmers took their oats themselves to the mill by horse and cart, and were willing also to take their neighbours bags of oats with them.

The flax mill employed a lot of local people as scutchers and beetlers of the flax. Flax was grown locally and at Dungooley, Co Louth, just a mile away. At flowering flax fields with cornflower blue flowers on long, thin, delicate stalks was a sight to see! At harvest it had to be pulled from the ground, a back-breaking task. It was left to rot (retting) weighed down in flax-holes in a stagnant pool and creating the most awful stench. When it was judged that the stalks had separated it was brought to the mill to be scutched and beetled. Then it had to be bleached on bleach-greens. Men from the mill used to go door-to-door to collect urine from chamber pot for the purpose! The ammonia did the job! The final product, linen, became the staple product of Ulster. Expensive to buy, it was made into bedwear, tablecloths, underwear and the like. These were sold abroad where people could afford such luxuries.

Today mills are found only in large towns or cities. Linen making is a smaller, specialist enterprise and almost all local, rural mills have closed. It was the increasing popularity of the more versatile and softer cotton cloth that caused the linen trade to collapse.

Forkhill retains its rural charm and much of its traditions. Don’t miss out on it in your travels through South Armagh!