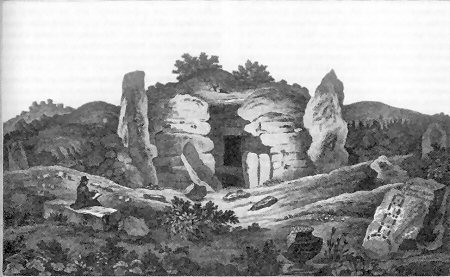

This Pillar Stone just to the north-west on the Slieve Gullion Ring Dyke is a menhir, – a tall, upright stone that once formed a tiny part of the Annaghcloughmullion cairn, an edifice in its time worthy of those at New Grange, Howth and Dowth in the Boyne Valley.

History

Archeology of the Carlingford Lough Region

The most recent Ice Age, which lasted in this region from c.30,000-12,000 years B.P. not only determined the topographical character up to the present, but eradicated almost all archaeological evidence of earlier habitation.

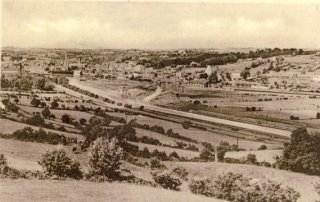

Linen Industry in Newry

Newry was late on the scene in establishing powered flax mills, exploiting the boom that inevitably followed the closure of American ports during their Civil War.

Nicholas Bagenal 1509-1590

The much quoted Nicholas Bagenal 1509-1590 (the first of that line to come to Ireland) was born the son of John Bagnall, Mayor of Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, England and Elinor, daughter of Thomas Whittingham of Middlewich, Cheshire, England.

Bishop Carroll and Irish Labour

On this date in 1961 the Newry Reporter carried a story of a presentation to newly-created Bishop Carroll who was, the next month, to be consecrated Bishop of Monrovia (

In the hands of the enemy

After the order for surrender came, we were marched to O’Connell Street and halted between Parnell’s statue and Nelson’s Pillar. Each volunteer laid his arms and ammunition in front of him. We were then eased off from our original positions to make room for further Volunteers.

Tom Kelly, Labour Champion

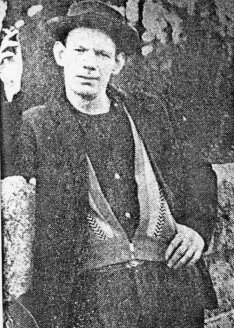

Patrick Rankin, Newry Republican

Patrick Rankin was the only Newry person to take part in the 1916 Rising. He cycled to Dublin to join the rebels in the GPO in Sackville Street. 32 years later he wrote his memoirs.

Robert McGladdery

The Last Hanging In Ireland

The trial captured the attention of the general public and Lord Justice Curran presided throughout. Pearl Gamble was found strangled and stabbed in a field near her home in Upper Damolly, Newry on Jan 28th after attending a dance at her local Orange Hall.

Her dead body had been dragged or carried across three fields before it was left partially concealed in a clump of whin bushes at a place known as Weir’s Rocks at Damolly. Mc Gladdery who had danced twice with Pearl that night denied having any part in the killing.

This was part of the ‘speech from the dock’ – certainly not one of the classics of the genre – by Robert Andrew Mc Gladdery who was found guilty of the wilful murder of 19 year old shop assistant Pearl Gamble.

The speech came after a jury had returned a guilty verdict on the seventh day of his trial on October 16 1961.

He claimed that after leaving the dance hall he walked home alone by the Belfast Road. He had been in the witness box for almost six and a half hours in an attempt to save himself from the hangman’s noose.

His defence was conducted by Mr. James Brown Q.C. and Mr. Turlough O’Donnell (instructed by Luke Curran of Newry). Turlough O’Donnell , originally of Bridge Street Newry, later became Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland.

The defence took 100 minutes in their closing address. At the end of this Mr. Brown asked the jury to retire to their room and ‘weigh well all these grave matters,’ and bring in a verdict which the defence submitted would be the proper one – Not Guilty. The Attorney General, Mr. W. B. Maginness, with Mr. C. A. Nicholson Q.C. and Mr. R. J. Babington appeared for the Crown.

Their address took 80 minutes to deliver and they submitted that ‘if the jury was satisfied beyond all reasonable doubt that on that awful morning of Jan 28 the man in the dock killed the young girl in a ghoulish fashion, then as men and citizens, helping in the administration of justice, they must do their duty and bring in a verdict of guilty.’ Although no-one actually saw the killing there was a lot of circumstantial evidence and a number of witnesses were called to testify to prior events on that fateful night.

The point of what clothes Mc Gladdery had been wearing on the night of the murder was investigated in great detail during the trial; in particular, the articles of clothing which corresponded in description to those which witnesses claimed Mc Gladdery had been wearing at the dance and were subsequently found hidden in a septic tank (close to the scene of the murder).

There were thirteen witnesses and although some disagreed about the exact colour all agreed that it was a “light suit”. Mc Gladdery denied he had ever owned a light suit and claimed he wore a blue suit at the dance. He later tried to implicate his pal, Will Copeland, by claiming that he had loaned him some clothes similar to those which were discovered in the septic tank.

Copeland, it emerged from evidence and on the trial’s completion, was entirely innocent of any involvement in this heinous crime.

In his week of ‘freedom’ when he was being trailed by RUC detectives wherever he went, McGladdery contacted the press about ‘police harassment’. It was probably an ego trip on his part. He managed to have an interview with him printed in the “Daily Mail”, where he ranted on about being followed by the police.

I remember especially he was photographed stripped to the waist holding home-made weights (metal bars with big moulded chunks of concrete on the end). “This man is a fitness fanatic.” In the early stages of the trial, his lawyers tried to impute that a fair trial was impossible, because of the previous press publicity.

Pearl Gamble

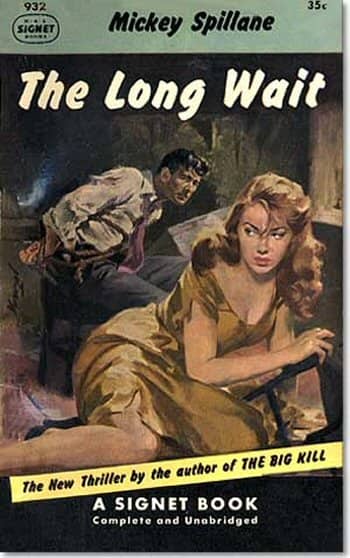

I also remember hearing in evidence that the weapon was a triangular-cross-section file which, it was proved, was bought by him in Woolworth’s in Hill Street. A Mickey Spillane book of McGladdery’s – The Long Wait – was produced as evidence, because it had about thirty puncture holes in it, claimed forensically to have the same dimensions as Pearl Gamble’s wounds. He was said to have practised his stabbing technique on it.

Lord Justice Curran took two hours summing up. The courtroom was crowded and many more stood outside unable to gain admittance. After 40 minutes of deliberation the all-male jury brought in a guilty verdict.

Lord Justice Curran fixed the date of the execution for November 7th.The defence counsel immediately entered an appeal on Mc Gladdery’s behalf. Back in prison Mc Gladdery wrote a sixteen page autobiography which was submitted to the Cabinet as part of his appeal.

All his attempts at avoiding the hangman failed and his execution was re-scheduled to take place at 8.00 a.m. on December 20. Before eight o’clock Mc Gladdery sat in the condemned cell and for the first time since his arrest, and perhaps realising that he might soon be facing his Maker, and after listening to the advice of his religious ministers, he confessed to the murder of Pearl Gamble. After the trial was over, it was revealed that he had a prior record of sexual and physical abuse of young women.

Prior to McGladdery, the last to hang in Ireland was a Limerick man in 1954. In 1964, three years after McGladdery, two murderers were hanged (at roughly the same time) in Liverpool and Manchester. This ended capital punishment in the U.K.

Total number of executions in Northern Ireland during the 20th century : 16.

| Date | Name | Prison | Victim(s) |

| 11/01/1901 | William Woods | Belfast | Bridget McGivern |

| 05/01/1904 | Joseph Moran | Derry | Rose Ann McCann |

| 22/12/1904 | Joseph Fee | Armagh | John Flanagan |

| 20/08/1908 | John Berryman | Derry | William Berryman, Jen Berryman |

| 19/08/1909 | Richard Justin | Belfast | Annie Thompson |

| 17/08/1922 | Simon McGeown | Belfast | Margaret (Maggie) Fullerton |

| 08/02/1923 | William Rooney | Derry | Lily Johnston |

| 08/05/1924 | Michael Pratley | Belfast | Nelson Leech |

| 08/08/1928 | William Smiley | Belfast | Margaret Macauley, Sarah Macauley |

| 08/04/1930 | Samuel Cushnan | Belfast | James McCann |

| 31/07/1931 | Thomas Dornan | Belfast | Isabella Aitken, Margaret Aitken |

| 13/01/1932 | Eddie Cullens | Belfast | Achmet Musa |

| 07/04/1933 | Harold Courtney | Belfast | Minnie Reid |

| 02/09/1942 | Thomas Joseph Williams | Belfast | Patrick Murphy |

| 25/07/1961 | Samuel McLaughlin | Belfast | Nellie (Maggie) McLaughlin |

| 20/12/1961 | Robert McGladdery | Belfast | Pearl Gamble |

All were for murder. There were twelve executions at Crumlin Road prison, Belfast, three at Derry and one at Armagh. (A total of seventeen men were hanged at Crumlin Road prison between 1854 & 1961).

Albert Browne, a member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), was found guilty of killing a member of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in October 1972 for which he was sentenced to death but this was later commuted to life imprisonment.

William Holden, who had killed a soldier, was the last person to receive the death sentence in Northern Ireland and his was also commuted. The death penalty was later abolished as part of the Emergency Provisions Act.