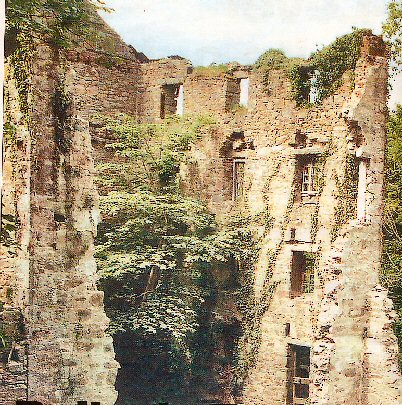

This historic building, on the way into Bessbrook was recently demolished. There are very few remaining anywhere in the district. They were located close to rivers where water could be diverted and utilised as a source of power.

Industrial History

The great estates

Small farms continue to predominate in the Ring of Gullion, though fewer than before of those who occupy them any longer practise agriculture as their first occupation. Still their use, or former use, has shaped the landscape.

Fews Mines and Forests

Newtownhamilton, says an old copy of the Armagh County Guide, is named after its founder who in 1770 established a settlement here in the

Butter Market: A Short History

The Butter and Egg Market was erected in 1874 in Market Street, at the foot of High Street. I shall have to make a return visit to my friend, Ben Hughes who still resides in the locality, to revive my memories of those few details of it that he shared last time with me.

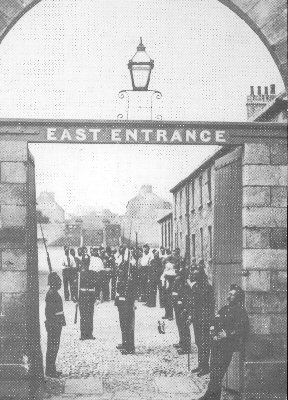

Newry Military Barracks

Poor Law and Tramps

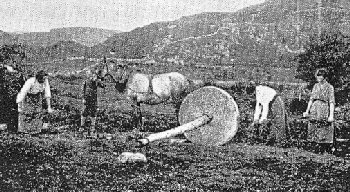

Ballagh Millstone

On the edge of the Calliagh Berra’s lake on the top of Slieve Gullion is a massive millstone, clearly recognizable in the photo from its circular shape and the hole in the middle. I’ll tell you the story and it’s the God’s truth, for indeed any other attempted explanation would be preposterous.

There was a time when the milling of corn was one of the chief, and indeed the most lucrative enterprises in the country. People have to eat, don’t they, whether in war or in peace? And the owner who has the hardest, and most long-lasting and largest millstone, capable of grinding the greatest quantity of wheat in the shortest space of time and over an extended period of many years, clearly would have the advantage over his rivals.

There was a mill in the Ballagh district one time in need of a new millstone and the owner, one Peter O’Mara was determined to outshine his rivals. He knew that the granite stones that made up the stone-age passage grave on top of Slieve Gullion could not be beaten for their hard and long-lasting qualities. He cared nothing for the customs and long-held beliefs that these graves should not, at any cost, be interfered with. In the middle of the night – for despite his callousness, he cared not to let his neighbours know the source of his new millstone – he arranged to have one of the largest and appropriately shaped granite rocks removed and transported to his mill. It took little shaping to turn it to its new purpose and in no time at all, it was grinding out meal by the ton. Peter’s mill thrived for many a day and he became rich.

But like all before him and since, that dared to interfere with things of the ancestors, bad luck plagued him thereafter. Though his mill thrived, his cattle and indeed his family did not. His cows were dropping off with all sorts of disorders and over the space of a few years he lost his wife and three of his children to strange diseases. It was an oul’ neighbour woman that suggested to him that maybe he had done something to bring the curse of the gentle people upon himself. Then he knew.

He arranged, as fast as he could to right this wrong. But it was easier for the oul’ donkey to carry his heavy load down the mountain than it was to carry it back up again. He was but two hundred metres from the passage grave, at the side of the Calliagh Berra’s lake, when he dropped down dead and the millstone landed in its present location.

But no more harm came to Peter for his intention was good.

And if you can think of a better explanation why that stone is there, well, I’d like to hear it!

Damolly Mill

Up until a generation ago if one was fortunate enough to find work locally as likely as not one worked in the mill.

Damolly Mill closed down twenty five years ago, in 1979. For almost two and a half centuries it – under different guises – had provided employment and community life for ten generations of local people.

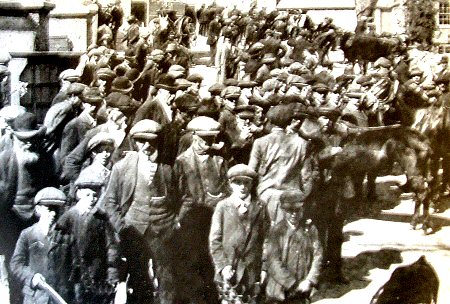

Kevin McAllister’s Hiring

I lived outside in the barn in the first house I was hired to, said Kevin McAllister. If you didn’t finish your six months you could be done out of your money. There was no law to back you up. It was rough enough. They took three 2.5d stamps off me, for the letters I wrote home in that time. And 7d for plasters for the boil on the back of my neck.

Was there any difference working for Protestant compared to Catholic employers?

You were treated as well, if not better, by the Protestants. With them there was no work on a Sunday. With your own the real work only started on a Sunday! ‘Seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day, and the rest of the time’s your own!’ What kind of work?

Cleaning drains, carting out muck, harrowing (2-3 horses), you were often in sheughs to the eyebrows [I think that’s what he said!]

My next job I was paid