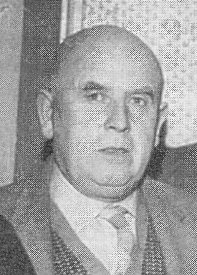

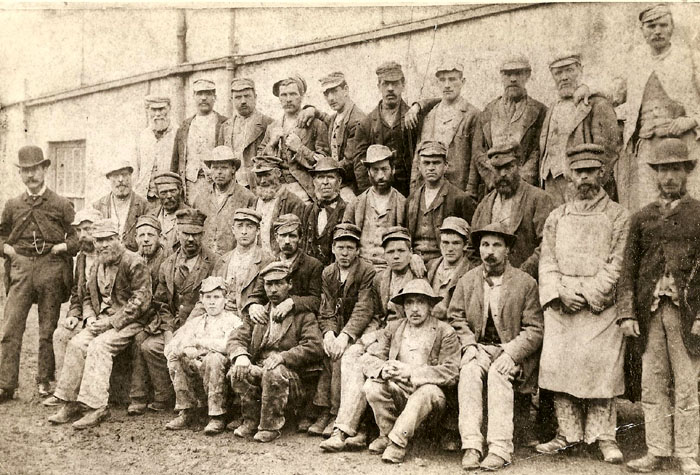

When the Irish Citizens Association won the day at the Council elections of 1949 – and continued to dominate local politics here over the next decade – the sole surviving Labour voice was that of Tom Kelly (pictured here). Single-handedly he championed at Council level the cause of the poor, deprived and oppressed of the town over that decade, because the populist green Tories led by Max Keogh and Joe Connellan were more interested in flag-flying and coat-trailing and self-advertisement in Keogh’s Frontier Sentinel.

The change began when Irish Labour won a clear-cut victory at the 1958 elections. Tom Kelly became chairman and enthusiastically led the social and housing reforms that were to quickly transform our town. The major house-building programme that had begun with The Meadow and Dromalane Estates was accelerated. Kelly, though a shy and quiet man, was an inspirational character and encouraged other Labour men of conviction and quality to follow his way. Thus after Tom’s retirement and early death we had leaders such as Tommy McGrath and Hugh Golding.

Tom Kelly was born in Newry in 1903 the only son of Michael and Margaret (Larkin). As a young man he was inspired by the writings and the life of James Connolly and he was a volunteer in the War of Independence. He was arrested by the Black and Tans along the railway line in Newry on 23 May 1921 and suffered a severe beating which left him with a lifelong hearing defect. He was sentenced to 15 years for possession of firearms but later benefited from a general amnesty.

In jail the contemplative life inspired his faith and on his release he in 1924 joined the Jesuits. His six years in the order strengthened his faith again and his conviction that peace and justice must be pursued through non-violent means.

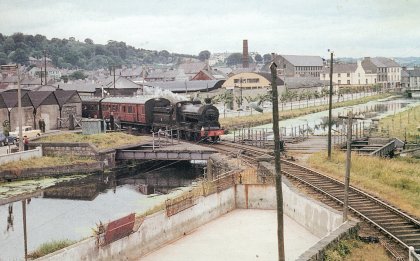

Working as a carpenter in Dublin he often returned to Newry and on one such visit he met Sarah O’Gorman of Damolly whom he would later marry. The new Mrs Kelly wanted to live in Newry and on his return Tom gained occasional employment at the Docks in Newry, Warrenpoint and Belfast. In Newry they lived first in High Street and then, for the next thirty years at Rooney’s Terrace.

Through all these years Tom worked on behalf of the working class, helping to fill out claimant forms, for example, for the unemployed who needed such help, fighting tribunals for the redundant and championing the cause of the poor. He became a regional representative of the Woodworkers Union and took an active part in the wider Trades Union movement. It was not till he heard an address at Newry Town Hall in 1943 by the famous Jack Beattie of Belfast that he joined the Labour movement.

When the Labour Party split at the end of that decade over the declaration of the Irish Republic, Tom held fast to his convictions and remained with the Irish Labour Party. Thus it was that he was elected as the only Labour man to the Ballybot ward in that year’s elections. Among those who canvassed for Tom was Turlough O’Donnell, son of the well-known Labour activist and who himself would rise to become High Court Judge of Northern Ireland. (When last I heard, Turlough, an interesting and obviously very articulate man, was living in retirement in Blackrock).

For the next ten years, though the ICA blocked his membership of key committees at every turn, Kelly’s reputation as working-class hero only grew and he topped the poll at a number of subsequent elections. He championed the use of a merit points system for the allocation of houses before any party adopted this as policy. He opposed the building of further sub-standard ‘orlit’ homes and called for the total removal of slum housing. The Labour Party, and Kelly in particular suffered from the breaking of a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ in 1955 that saw the rise and election of Joe Connellan to the South Down parliamentary seat and deprived our people of the voice for social justice we deserved on that wider stage.

The election of 1958 saw Tom Kelly become Chairman of the Urban Council and Newry’s first citizen. A bitter split in the ranks in 1962 affected Tom’s already poor health. Despite the onset of Parkinson’s Disease he contested a final election in 1964. He remained Chairman of the local Irish Labour Branch and saw it successfully reassert itself against Tommy Markey’s dissident Newry Labour.

Despite a stroke he attended the famous first Civil Rights Marches in Newry. On 12 April 1969 at age 65 Tom Kelly died. A member of the National Graves Association contributed a tricolour to his widow to adorn the coffin, in tribute to his lifelong patriotism. Stephen Ruddy, an Irish Labour colleague brought a Starry Plough. This became the flag of preferment for a man who had dedicated such a large part of his life to the Labour movement.

May this working-class hero long be remembered.