This couple had a wee holding in the West of Ireland and a locka acres of land, a small house and in the first year of their marriage they had a baby. very long ago!

Folklore

Fairy Funeral

‘I know you don’t believe in fairies. I don’t believe in them myself. Though they’re there. Just the same!

Finn and Calliagh Berra

‘It’s very gentle country all aroun’ here but I’ve been to the other side of Slieve Gullion where they had giants and witches as well.

Did ye iver hear of Finn McCool? Well, there’s some say it wus he and not the Calliagh Berra who threw the White Stone of Dorsey. But sure mebbe both had a han’ in it, for they were both upon the earth togither. An if he wus fleet o’ foot an’ strong of limbs, she wus strong in spells.

Do ye know her house on the mountain an’ the lake beside it? Sure it was into that very lake she coaxed fool Finn. An’ in he went fresh an’ youthful an’ out he come a done oul’ man. An’ they had a high time making him right again.

Often I started up the mountain to see the lake but I cud nivir head the whole road, I wus so afeard, for ye know a wedding party went into her house once, an’ they turned till stone. Her house goes down and down an’ in the bottom chamber sits the Calliagh Berra herself till this very day. Ay an’ will, till the end of time.

But where Finn is I know not, or if I do, I disremember’.

Oxtercogged with Fairies

‘Grimes oxtercogged [went arm in arm, was intimate] with the fairies often. He’d be in conversation with them and people wud hear him talking till them, but he’d always deny it. Many a time going till the well he was aheared tellin’ them to keep off him. He was a wee bit of a man: she was six foot, and he’d even deny it to her.’

‘Cows were sometimes elf-shot when I wus wee. I mind a man cud cure the bother. He’d take a bit of kindled turf from the fire be the tongs an’ move it from side to side an’ say a bit of a prayer. It wus then put under the cow’s nose an’ she wus soon better.’

‘Me gran’father minded a fight at the graveyard gate between two funerals that arrived tillgither. It wus a hell of a scrap by he’s account. They went for each other like Turks, all because of a notion that the corp that was through the gates first wud hev the other bludy fella to chop and carry him.

People wur quare in them days – why if oul weemin had water till throw out at night they’d be afeared to do it in case it wus hurtful till some one, but whether it wus ghosts or fairies they wur afeared of I haven’t a notion. An’ if he went for a walk in the graveyard an’ tripped on a grave it wus bad, but heaven help ye if ye spread yer length in such a spot. Ye might just as well go home an’ make yer will.

Many a grave wus hoked [reopened] in the oul’ days, an’ not be people wantin’ bodies for doctors at all, but be people wantin’ skins for charms. It’s a pity till God ye wurn’t here in me gran’father’s time. He knowed it all.’

How can you let speech like this die out? When did you ever hear such verbs as ‘oxtercogged’ and ‘elf-shot’? Eh?

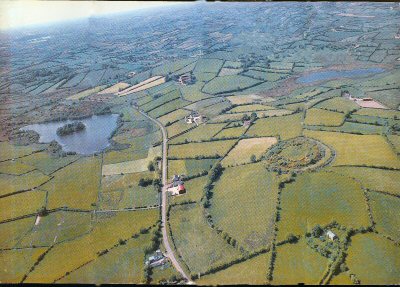

Lisleitrim Fort

At the top of the picture are the townlands of Drumlougher and Kiltybane with Lough Patrick on the left. On the right middle is the famous three-ringed Royal Fort of Lisleitrim. There was once a souterrain on its top level but – though still existing – this has been filled in with soil.

South Armagh Sayings

George Paterson, folklorist and archivist, collected sayings of the aul people as he travelled the country. Here is a selection.

‘A crowd of hares used till gather in the wee forth [fort] at night. They used till just sit there an’ even the ‘grue’ [greyhound] that cud see them well wud luk the other way. Me gran’father himself went in once when they were there. He saw the lot of them in the centre of the ring. But when they saw him they slipped into the sheugh at the forth. As soon as he left they were back on the rampar [rampart]. He was sorely bothered be them an’ one night he borrowed a gun an’ let them have it. [shot them with it]. An’ sure as yer here the nixt mornin’ there wus hardly an oul’ woman that wusn’t in bed.’

‘A man about here once followed a fairy funeral. He wus up late at night an’ heard the convoy comin’. He slipped out an’ followed them an’ they disappeared into Lisleitrim Fort. He heared the noise of them walking plain but he saw none of them.’

‘They wur goin’ to break up the forth in the days of my forebears but when the horses and plough wur upon it, a slice of bread was thrown right in front of them. It wus a strange thing to happen an’ they were bothered, but a wise woman told them that if the place wus left alone the Nugents would niver want for bread. An’ thank God we niver did even in the Famine time. It wus always a right fairy place.’

P.S. from Editor: Wudinye think, with a roughage like that in the family, that Peter Nugent cud buy his round, now and then?

Travelling Woman

Have you noticed the absence of street ‘characters’ over recent decades? If it wasn’t for Bearded Marty, ever present at all hours of the day and night, we’d have totally lost all ‘local colour’ – as my schoolmaster used to put it! Stop and chat with him some time – he’s got an interesting life style and a good line in craic.

The Art of Storytelling

The storyteller’s art is a dying skill. There was until recently (there may be still, for all I know) a Newry Storytellers Group. I am a fan of the old style. My uncle was a storyteller from Sheetrim, as was his father and grandfather before. The custom belonged by the fireside of the old-style ceili house where neighbours gathered of an evening to while away the long winters’ nights. The only surviving such home that I know of is that of my dear friend Sarah Hagan, extolled elsewhere in these pages. I know of a few survivors of the storytelling genre, most notably John Campbell of Mullaghbawn [and his mate, Len Graham, and their friend Mickel Quinn]. Terry Conlon tells the odd yarn at the Thursday night Railway Bar session. Jack Lynch of Cavan is good too and there are others. In Rostrevor of a Wednesday evening (8.30 – 10.30 Rostrevor Inn, we have Alfie Corr, Kathleen Lucas and Dominic Bennett. The one I am about to tell belongs to Jack.

Perhaps the first requirement is the accent. I am hopeless for I’ve been cursed with a town accent that is totally unsuitable! Worse, I cannot assume any other accent. To my ear, it has to be a broad South Armagh lilt, or at worst, Midlands or West. The far South (Cork/Kerry) is probably good too, but no one can understand them but themselves. They must have the rare laughs at everyone else’s expense!

It helps enormously to have a seasoned, world-tired face (sorry, Terry!) with a permanent comical expression. Only the twinkling eyes can betray the teller’s real message. One must not laugh at one’s own jokes! The art probably developed as a defence against the jibes of the foreigner who loves to assume abject ignorance in all natives. The storyteller plays the assumed part with practised finesse. The foreigner, confirmed in his prejudices, departs, feeling totally vindicated with his jaundiced opinions. Behind him, everyone is roaring at his gullibility.

Many stories tell of the helpless traveller, normally a real amadan, who was a common enough figure in Ireland of previous centuries. Jamesy, the uncle, told of one such. He was cursed with an inability to properly express his emotions and constantly said the wrong thing!

He was walking the Bog Road one day when he came upon two men stuck fast in the bog hole. He roared and laughed and merrily wished them Good Day, as he had previously been advised. One man escaped from the quandary, came over and loudly scolded him for his intemperance.

‘What should I say?’ asked the amadan.

‘You should say ‘The one’s out, may the other soon be out”, he was chided.

Of course, the next poor man the amadan met on his travels had suffered a serious accident, where one of his eyes was totally removed from his head.

‘The one’s out, may the other soon be out!’ he roared gleefully.

In the story, these scenes repeat for up to twenty minutes telling. The simplicity of the twists is an essential device. The art is in the telling, and frankly, one should never commit to written words such a unique art form. I was recently given a book of Old Irish Songs, without the music. I can sing those I know. The rest read like insufferably bad poetry. Think of The Meeting of the Waters without that beautiful air. Despite this warning to myself, I am about to proceed. My justification is that there are hundreds of exiles out there who have never, and will never hear them being told as they should be. Please imagine the slow, heavily accented telling, the heavy pauses between phrases [if I wrote these in, it would spoil the imaginings] the twinkling eyes, the build-up, the throwaway punch lines, the look of bewilderment on the teller’s face that people should see the funny side of a very serious situation!

You might have heard it said by some that the South Armagh people are a bit mane – a bit tight, as they say here – but there’s not an ounce of truth in that: not a single ounce at all! – In general, that is.

In fact the only mane man I ever knew from that area was P J Brannigan from the parish of Sheetrim, in the townland of Creggan, near the village of Cullyhanna. A few miles from Crossmaglen. Have I got you located yit?

Anyway I called to visit his house wan Sunday mornin’ and wasn’t P J watching the mass on the television. And what am I going to tell ye only, when it came to the Collection time, didn’t he turn the television aff?

Another time I called hoping for a bit of a feed – seeing it was about lunch time. The mother was within, but P J was without. Out standing in his own field. Acting the scarecrow. He looked the part. He had bits of straw stuffed up his sleeves and up his trouser legs.

But he had to come in to lunch, and that’s when the crows had a bit of a feed to themselves too. P J was sitting there at his dinner and I was sitting across the table from him. Hoping for a bit of grub. The mother – she’s passed away now, God rest her – asks me would I like a cup of tea in me hand. I would, says I.

Well, she nearly scalded the hand af me!

Then I’m sitting there a long time, me elbows getting caul’ from the oilcloth on the table, till I spake up.

‘Are ye still baking yer own bread, Mrs Brannigan?’ says I, wily enough, though I say it meself.

‘Ach, I am for sure’, says she. ‘I suppose you’d be liking a cut af it?’

‘Well I wouldn’t say no’, says I. She cut me af the heel of the bread and left it down bare on the table there in front of me. I waited a while.

‘You’re probably still making yer own butter these days’, I offered with a smile.

‘You’d like a wee dab of butter?’ says she, not slow like.

It was a very wee dab of butter and I had to use my finger to spread it on the bread.

I sat another while and me not eating yet.

‘Would you like a bit of honey?’ says P J.

Well, he gave me a wee spoon of honey – and when I say a wee spoon, I mean it wasn’t even the size of an egg spoon. You’d maybe get a wren’s egg, or something on it. The wee-est dab of honey you ever seen. I looked a while and then I says,

‘I see you do be keeping a bee!’

I’ll tell you the rest of Jack’s story next time.

Biddy Hanratty

Bridget Hanratty, the last of our local Travelling Women, came to the door well equipped to receive the ‘charities’ that were happily and freely offered. Despite this, she protested loudly when she was given money, or a few eggs, of a bowl of flour or meal, and potatoes for her sack.