John Mitchel (1815-1875) was a Young Irelander leader and perhaps the most esteemed republican to come from Newry. He was born in County Derry near the town of Dungiven on November 3 1815.

His father was a Presbyterian Minister and was called to serve in Newry. The family moved to Drumalane House.

Young John went to the school of Dr Henderson in Hill Street along with his life-time friend and soon to be relation John Martin, another Newry republican hero of Presbyterian stock. In the mid 1830s Mitchel graduated from Trinity College Dublin and was sent to Derry to work in the law office of his uncle.

It was about this time that he met and married Jenny Verner of Newry, the daughter of a ship’s Captain. They remained happily together (when not separated by enforced exile) until John’s death, thirty eight years later. In 1840 John Mitchel was sworn in as Attorney at Law. His church minister father died the same year. John and Jenny moved to the Banbridge area where he worked as a partner in the firm of Frazers. Mitchel worked hard at his legal practice, gaining a high reputation from all communities.

Our country was reeling from the punitive fiscal, trading, economic and financial measures introduced by the Imperial Government under the Act of Union designed to permit unfair advantage to England over Ireland in these areas. Organised resistance had been dealt a fatal blow by the massacres ordered in the previous generation against the United Irishmen and their supporters of the 1798 Rebellion. Few were prepared to raise a voice in protest.

John Mitchel entered the political arena when he began writing for the Young Irelander newspaper ‘The Nation’. In 1846 he replaced Thomas Davis – that other great resistance hero – as leader writer for the paper and the tone became immediately much more belligerent. For the following two years leading up to the 1848 uprising, Mitchel wrote nearly all the paper’s political articles, invoking the hatred, wrath and finally reaction of the government while becoming the darling of the republican movement throughout the country. These writings reveal Mitchel’s writings at their best, surpassing even those of his illustrious predecessor.

The famine conditions of the 1840s had a profound effect upon him. The sight of his fellow countrymen sunk in the horrors of starvation, extreme deprivation or forced into impecunious exile left an indelible mark upon him. Travelling in Galway, he observed scenes that, he acknowledged, would never leave the memory of any observer. He wrote of

‘Cowering wretches, almost naked in the savage weather, prowling through turnip fields, endeavouring to grub up roots which had been left, but running to hide as a mail coach rolled by; very large fields where small farms had been consolidated, showing dark bars of fresh mould running through them where ditches had been levelled …. …sometimes I could see in front of the cottages, little children leaning against a fence when the sun shone out – for they could not stand – their limbs fleshless, their bodies half naked, their eyes bloated and yet wrinkled and of a palish green hue – children who would never, it was too plain, grow up to be men and women.’

Again in Jail Journal, he wrote …

‘Our footfalls rouse two lean dogs that run from us with doleful howling, and we know by the felon-gleam in their wolfish eyes how they have lived after their masters have died. ..these people were our hosts two years ago.. they shrank and withered together until their voices dwindled to a rueful gibbering and they hardly knew one another’s faces, but their horrid eyes scowled on each other with a cannibal glare. We know the whole story – the father was on a ‘public work’ and earned the sixth part of what would have maintained his family which was not always paid to him. But still it kept them half alive for three months so that instead of dying in December, they died in March. And who can tell the agony of those three months? … five children all dead weeks ago and flung coffinless into shallow graves – in the frenzy of their despair they would rend one another for the last morsel in that house of doom; and at last, in misty dreams of drivelling idiocy, they die utter strangers.’

John Mitchel, Jail Journal, 1854.

Mitchel called for violent, direct, military action to be instigated to drive the English out of Ireland. His open advocacy of armed rebellion was not supported by his more cautious, constitutionally minded colleagues so Mitchel left ‘The Nation’ early in 1848 and established his own radical newspaper ‘The United Irishman’. Through this he called for the overthrow of the landlord system and the establishment of an Irish Republic.

Three and a half months after its first publication, Mitchel was arrested by a frightened and uneasy government. It rushed through a special law at Westminster designed to deal specifically with him. This was the Treason Felony Act. John Mitchel was convicted by a packed jury and sentenced to fourteen years transportation. Without him the Irish rebels, weakened by three years of famine were unable to spark support from the defeated and disillusioned people and the Irish Rebellion of 1848 was the least successful of all those rebellions that swept Europe in that fateful year.

Mitchel was first exiled to Bermuda. A year later he was moved to Cape Colony and finally to Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) where he lived under parole, until he escaped to America five years later. He was well received by Irish exile in New York where he again established a successful paper ‘The Citizen’. Unfortunately in the American Civil War of the mid-sixties, Mitchel supported the Confederacy and the cause of slavery.

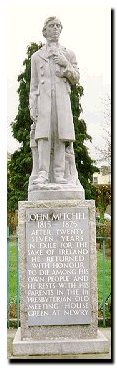

In 1875 Mitchel returned to Ireland and won a parliamentary seat in Tipperary, under an abstentionist ticket. His health had deteriorated and he was spending much of his days bed-ridden in Dromalane House. He died peacefully on 20 March 1875 and was buried alongside his parent in the Presbyterian Old Meeting House Green in High Street, Newry. His friend (Honest) John Martin caught a chill attending his funeral and himself died a few days later.

Mitchel’s surviving oeuvre – besides his newspaper articles – include ‘Jail Journal’, ‘Last Conquest of Ireland’, ‘Life of Aodh O’Neill’, ‘Crusade of the Period’ and ‘A History of Ireland’. A statue in tribute stands in St Colman’s Park and many political and Gaelic clubs of the town have adopted his name in honour.

There remain, even in our town those who call themselves Irish, who know this to be a valid record, and still choose to excuse the Imperial Government, to explain the ‘poor’ landlords’ heartlessness, to argue ‘laisser-faire’ economics, to defend the Union, to vilify Mitchel in other fields of thought and endeavour.

In the American Civil War he sympathised with the South, lost two sons in the fighting and was for a short while imprisoned by the victorious Northern forces. He went to Paris where he observed his much-loved daughter Henrietta (Henty) – who had become a Catholic – die while still at school.