The most famous graveyard in all our area is doubtless that of Creggan, just outside of Crossmaglen, not least because it is the last resting place of the celebrated Bards, Padraig Mac a Liondain (1685-1733), Seamus Mor MacMurchadha (1720-1750) and Art MacCumhaigh (1738-1773).

The grave of Mac a Liondain is marked by a plaque erected by Eigse Oirialla, an organisation harking back to an even earlier period when the clans of Armagh, Monaghan, East Fermanagh, South Tyrone and North Louth were united under the great House of Oriel. (The name too is commemorated in the beautiful Oriel Trail, a glorious walk well-signposted through the magnificent Cooley Peninsula!).

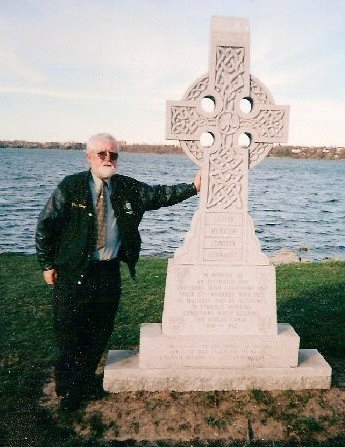

McMurphy has been already lauded on Journal. This present article is about MacCooey. Local tradition has it that MacCooey penned his greatest work, ‘Urchill an Chreagain’ after spending a night in the underground vault at Creggan that houses the bones of his former clan chieftains, the O’Neills of the Fews. The O’Neill clan vault (marked now by a simple granite stone bearing the inscription ‘1480 O’Neill 1820’ – the dates representing their span of dominance – a time of culture and native powers when the said poets were the pride of the entire province of Ulster) was rediscovered only in 1971 by my aunt’s brother Owen Keenan when his tractor wheel sank mysteriously into the earth! Anyway MacCooey lapsed into despair for his conquered people in the vault: a fair maid appeared and invited him to accompany her to a land where the English did not rule. Convinced of his people’s defeat he agreed to go. He insisted however that wherever he might die his body would be laid to rest in Creggan.

MacCooey’s life was short and stormy. He was excommunicated by the local priest Fr Terry Quinn for having run off with his second cousin Mary Lamb whom he eventually married in a Protestant wedding ceremony at Creggan Church (which, apparently to some people’s surprise is still a Protestant church). MacCooey was ostracised by his neighbours and had to leave. He went to Howth where he composed ‘Aisling Airt Mhic Cumhaigh’ (which in English became entitled ‘By Howth’s Fair Haven’. In this poem he dreams of the memory of Creggan churchyard and the O’Neills which he imagines have been restored to The Fews. Of course, in his dreams Fr Quinn, his nemesis has been ousted.

As it happened the latter came to pass and the excommunication was lifted. Fr Quinn’s grievance with the poet was, it was believed, on account of a vicious poem that Art had written about his sister, the priest’s housekeeper. Apparently MacCooey had one time sought succour in the priest’s home but Mary Quinn had offered him only buttermilk and confined him to the kitchen, well away from some gentry then being regaled in the house. MacCooey in his verse brought her eyesight defect to attention and entitled the poem Maire Chaoch or Blind Mary. Fr Tom Fee’s translation includes the stanzas..

MacCooey the poet she reckoned unable

To drink with the gentry or sit at the table

But in some nook or cranny, left perched on his legs

He drained all his buttermilk down to the dregs.

If the heroes of Oriel were still in the land

They wouldn’t allow his verse to be banned

Nor suffer the hucksters to kick up a din

Entertained in the priest’s house by Blind Mary Quinn.‘

MacCooey has compelled to make amends to the lady and composed ‘Cuilfhionn Ni Choinne’ – The Fair-haired lass of the Quinns’. As O Fiaich said it is ‘a fulsome praise, metrically perfect and patently insincere!’.

It was enough to allow his return from Howth! He got a job as a cattleherd on a farm in Tullyard. A few years later he died and was buried as requested in creggan beside his sister. Remarkably her grave is marked while his is not.