History of Newry Workhouse [Part 2]

by

John McCullagh BA , BSc

Prior to the 1830s some little local Poor Relief was sporadically offered – mainly through the Churches – in almshouses to orphans and to the most destitute. Under the Poor Law Act of that decade a central Board, known until 1847 as the Poor Law Commission and thereafter as the Poor Law Board had overall responsibility for relief.

Newry Respondents to the Commission of Inquiry

The Irish Commission of Enquiry had been established to gauge the extent of need prior to the extension here of the provisions of the Poor Law Amendment Act. In 1836 it delivered its report into the condition of the poorer classes. The Report is available from the National Library in Dublin.

Much of the information was gleaned from responses to a questionnaire circulated to chosen prominent citizens in the regions. The questions put to witnesses reflect the attitude of their authors. So do the list of names and public stations of their selected witnesses. With the benefit of hindsight we might wonder whether these people could truly reflect society as a whole or testify to the extent of poverty (and to comment upon the reasons). The reader might decide for himself/herself after reflecting on the variety of answers given to identical questions. Considerable weight was given to this testimony when the Report was drawn up. For these reasons we quote from some of the responses of local contributors.

A number of prominent citizens represented Newry at the 1835 Inquiry. The local Presbyterian Minister Rev John Mitchell had recently come to Newry from Derry. Within the next decade his son John would qualify as a solicitor. Fired by outrage at the iniquitous British system, he forsook his practice to take up the Young Irelander cause. He went to Dublin and became editor of the revolutionary pamphlet ‘The Nation’ and championed the cause of Ireland’s poor until he was transported. His father’s testimony to the Inquiry too was sympathetic to the plight of Ireland’s poor.

Others testifying there included two justices of the peace, Mr Thomas Wearing and Mr William Thompson. A Mr Thomas Greer also gave evidence, as did the Rev John Kerr, a Protestant Minister and Rev Blake, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Dromore.

A number of the pre-determined questions seemed designed to blame the poverty of our citizenry on alcohol abuse, and such perceived ills as recourse to pawnbrokers’ shops. Some respondents did not always make clear on whose behalf they were speaking, or whether they were expressing the ‘common view’ or an authoritative opinion based on experience and verifiable fact.

An occasional question remained unanswered. Rev Mitchell offered no opinion on the number of public houses or the extent of illicit distillation in Newry. By contrast Mr Thompson J.P. alleged these were too numerous to count, were greatly increasing in number but deteriorating in aspect and were ‘a crying evil and certainly one of the most fruitful sources of poverty and crime’. He also considered the ‘thirteen pawnbrokers’ who dealt ‘exclusively with the very poor’ as ‘a very great evil now’.

Without the prejudicial comments, Mitchell concurred with the numbers. Pawnbrokers’ clients, he opined, also included ‘others in distress and want’.

Some few paupers, it is accepted, attempted to pawn stolen goods. Yet the modern mind may struggle to view the existence of so many pawnbrokers as indicative of moral turpitude on the part of any, save possibly that of the pawnbrokers themselves.

All the witnesses agreed that the numbers and condition in respect of food, clothing and shelter of the poor, to be deteriorating. The Rev Kerr thought to add that ‘their moral condition is chiefly to be deplored’. Mitchell remarked that ’employment and rates of wages had fallen much more than had (commodity) prices.’

All agreed that the parish was peaceable, with prosperous savings’ banks and benefit societies whose customers, mainly tradesmen, also included thrifty servants and people of humble means. Kerr and Thompson concurred that among the town poor there were instances of three or four families sharing the one cabin.

It was more common than they thought, averaging more than seven persons per tiny ‘entry’ house.

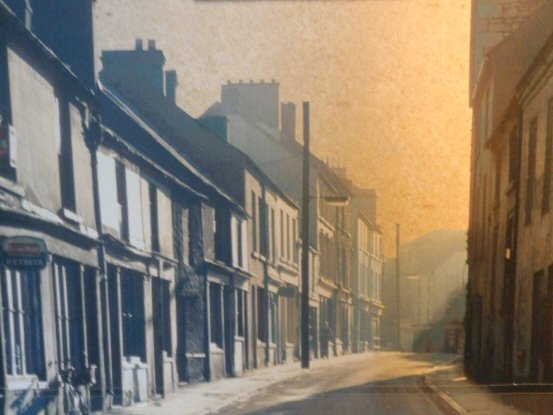

Conditions within these cabins or cottages were Spartan. Mitchell testified that they were owned and let by farmers in country areas, and by persons of some substance in the town who ‘built and let little houses to the labouring classes in backward streets’. The rent, more expensive by half in town though with no land attached on which to grow food, averaged around six pence a week. This was a substantial weekly expenditure for the poorest families at the time and beyond the means of those who had no employment to pay for it. In the country they generally consisted of two small apartments, in the town of one, very miserably furnished, often without bedstead or any comfortable bedding. The two JPs said they were ‘of the worst description’ and ‘not furnished at all’. In the country cottiers part paid for their rent through labour. In town they generally ‘hold of one person and work for another’.

When asked the number of acres in the parish and the rent per acre, the various witnesses betrayed their ignorance and/or willingness to hazard estimates as accurate facts. Kerr gave 9,690 acres, Mitchell 13,021 and Blake 8,436 though the latter referred only to the RC Church: he also ventured that arable and pasture land rented for much the same.