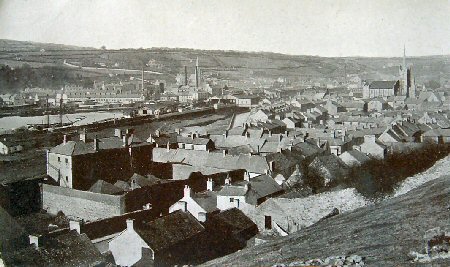

A scribe of recent yesteryear reflected on Newry of old, in the form of scenes from an imaginary walk through our fair streets then. I consider his musings worth repeating.

‘Let us first, in the company of a group of other wanton boys recently released from the stern discipline of Brother Dempsey at the Carstands School, disport in the waters of The Rampart. We wander through Pighall Loanan and over the Bishop’s Hill, vying with one another as to who will first dive into ‘Track Line’.

On the Downshire Road a bazaar for the benefit of local churches is being held. There are contests in music, drawing and many domestic arts. There is, particularly a Flute Band Contest with entries from Belfast and other towns. Michael Magill conducts St Joseph’s Band with Terence Ruddy and John Loy distinguishing themselves as instrumentalists.

A solemn procession leaves Dromalane House and passes along Dromalane Road, through Bridge Street and High Street to Meeting House Green, commemorating the funeral, a decade ago of the patriot John Mitchel. His widow Jenny Verner Mitchel, is just recently deceased in New York.

The mud heaps in Doyle’s Field have been levelled, grass sown and a road cut through its centre, for the Lord Lieutenant is soon to open an exhibition in the Needham Street Market. He will arrive by Edward Street railway station and we must clean up the ‘front door step’.

It’s Regatta Day in Newry. The Middle Bank is thronged with visitors and a goodly crowd is enjoying sports day in Greenbank. In the track event a bicycle race is about to start. The local riders, Dierson, McKnight, Graham and others, resplendent on their high velocipedes, are lined up when the appearance of a new entrant on a contraption with both wheels the same height, creates a laugh! Amid the general mirth a few strangers are circulating the crowd offering wagers that the Dublin stranger will win. The sporting elements among the townsfolk take the bets. It was Newry’s first sighting of a safety bike and the strangers reaped a rich harvest as it easily won. The local sports are sadder and wiser.

I pass, with some difficulty, through Monaghan Street. Both sides of the street, from Lamb’s Corner on the west to Magill’s Corner on the east, are lined with wagons that are full with groceries from the shops of McKnight and Renshaw and Dromgoole, and from Dickson’s provision store, adjoining ‘The Chestnuts’. The farmers standing in groups on the footpaths are jostled by laughing and carefree workers on their way to dinner from Dempster’s Mill, Wilson’s Mill, the Newry Foundry in Edward Street and Lupton’s Mill and Henry’s Brewery in Queen Street.

Coming to the Godfrey Bridge I stand and look north towards Sugar Island. A vessel opposite Beatty’s mill is discharging a cargo of Indian corn. A lighter is being loaded, further down, at the Salt Works, between the canal and the tidal river. Opposite Edward Street a vessel is discharging wheat for Felix O’Hagan’s Mill at the junction of Catherine Street and Edward Street. A little to the south a lighter is supplying coal to the yards of Mr Greer. Further north still, identifiable only by the familiar but distant sounds, another vessel is pouring out its load of golden wheat to be ground into flour in the fine brick mill of Mr Sinclair.

And now I turn south and look towards the Ballybot Bridge and the Buttercrane Quay. The scene is one of even greater activity. Opposite the premises of Carvill and Company, one of their own fleet of vessels is discharging a cargo of lumber, hewn in its own forests in the New World. The roadway along the canal is strewn with slate, sand, cement, and with steel for the manufacture of spades and shovels; wagons awaiting entrance to the yards are lined up as far as Magill’s Corner. Redmond and Company has a similar scene outside.

I walk south along the Quay. Again I am impeded by the milling crowds intent on purchase, and by mill hands from Dempsters and Wilsons, with those from the weaving factory on the Dublin Bridge and the Dromalane Spinning Mill, all returning for the afternoon’s work. My ears are dinned from the clang of iron and steel fabrication from Lucas’s Foundry on the opposite bank. Near the Dublin Bridge an overhead crane dips its steel buckets into the wheat-filled hold of a steamer and carries it aloft, across the street and into the maw of Fennel’s Mill. Another vessel is doing the same for Walker’s Mill in Mill Street – one of the first establishments of Europe, it is said, to have electric light of its own generating.

I cross the Bridge and come to Albert Basin and the sheds of the Dundalk and Newry Steampacket Company. A steamship lying at the wharf is taking on, by means of a gang of busy quay porters, a miscellaneous cargo with which the bulkhead and sheds are plied. There are slabs of granite and paving blocks, hewn from the Newry quarries that are destined to build the mansions and pave the streets of England; raw hides; finished leather from the many Newry tanneries; distilled spirits in cask, keg and bottle, from the warehouses of Matt D’Arcy and Company and Henry Thompson and Company; crated fowl and livestock for the Liverpool Market; bales of linen and linen yarn and other commodities manufactured in and near the town.

Further down the Basin, Spanish sailors, ear-ringed and swarthy, are swabbing decks of a barque that has brought sherry grapes from Malaga and other Iberian delicacies for McBlain and Company, Martin, Nesbit and Irwin, Kinnear and Lang, the Golden Teapot and The Golden Cannister.

Leaving the Basin and walking through William Street and up Hill Street – passing on the way the coach factories of Bannon and of Lawson – and then through Margaret Street and North Street, I find the same state of active business that was presented elsewhere. ‘

Newry was then a busy and thriving town, and mainly a manufacturing town.